Théo Fournier (European University Institute)

1 – Introduction

On January 26, French President Emmanuel Macron promulgated a new immigration law. This law, titled “Law to Control Immigration, Improve Integration,” came about nearly a year after Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin initially presented a draft to the Senate.

Like the other dozens of immigration laws adopted over the last decade, the aim was to address issues stemming from illegal immigration in France. Mr Darmanin hailed the bill as revolutionary and balanced, echoing Mr. Macron’s rhetoric of the “at the same time”: tougher border control and expulsion measures alongside a better integration of the lucky ones who can get a resident permit. The opposition did not share Mr. Darmanin’s optimism. The right and far-right criticized the integration aspect, while the left and far-left opposed the bill’s emphasis on repression.

The difficult political and social context postponed the discussion of the bill until November 2023. Following a month of intense political upheaval, Parliament finally passed the law on December 19th. One month later, the Constitutional Council partially validated it. Beyond signaling President Macron’s shift towards the right, the saga of the immigration bill underscored his determination to push through his agenda. He did not hesitate to manipulate the constitutional review process, potentially bolstering the populist and illiberal narratives of the right and the far-right.

2 – Political context – A bill on immigration at last!

The year 2023 proved to be one of the most tumultuous in recent parliamentary history. Early in the year, President Macron and then-Prime Minister Élisabeth Borne faced a significant setback as they struggled to secure a parliamentary majority for the pension bill. Ultimately, the bill was pushed through Parliament without a vote, utilizing the well-known procedure of Article 49, paragraph 3, of the Constitution. This move nearly led to the government’s downfall in March, with a motion of non-confidence falling just nine votes short of passing. After this episode, tensions in Parliament remained high. The Prime Minister continued to employ Article 49&3 (a total of 23 times in 18 months) to circumvent what she perceived as systematic obstruction from the opposition. Predictably, the opposition blamed the government for the deadlock. By the time discussions on the immigration bill started in November 2023, the government found itself more isolated than ever, lacking reliable political allies for passing its bills.

Gradually, the legislative journey of the immigration bill proved to be a bumpy road. The government introduced the bill in the Senate, knowing that the right-leaning majority in that chamber would push for its pro-restriction agenda. The government’s plan was to amend the Senate’s version during the legislative session in the National Assembly to appease its left-leaning party members. However, the bill never made it that far. Opposition parties united to pass a motion for preliminary rejection of the bill, effectively shutting down any discussion.

This left the government with a difficult choice: abandon the bill, handing a victory to the opposition, or convene a joint committee of the Houses to draft a compromise. The latter option, however, presented its own challenges. The right-dominated joint committee now wielded the power to reassert its pro-restriction agenda. Consequently, the final draft included measures even the far-right might not have dared to dream of: the abolition of ius soli, annual immigration quotas, termination of state medical assistance, and severe limitations on access to social benefits, among others.

On December 19th, the two Houses adopted the draft in identical terms. The political cost for Macron was high. A third of his deputies voted against the text and a handful of ministers threatened to resign if the text was promulgated as such. However, for Macron, the parliamentary vote was just one step. He intended to use constitutional review to strip away many of the sections added by the right-wing faction.

3 – The Constitutional Council’s decision

The day after the vote in Parliament, a shift in discourse emerged from President Macron and his troops. Suddenly, concerns were raised about the bill’s partial unconstitutionality, with certain sections deemed unlikely to withstand constitutional scrutiny. Did this justify abandoning the bill? President Macron argued otherwise, asserting that it’s not the role of politics to arbitrate on a bill’s constitutionality. A new strategy from Macron and his government became apparent: they allowed the right to incorporate its stringent measures into the bill, anticipating that the Constitutional Council would likely strike them down.

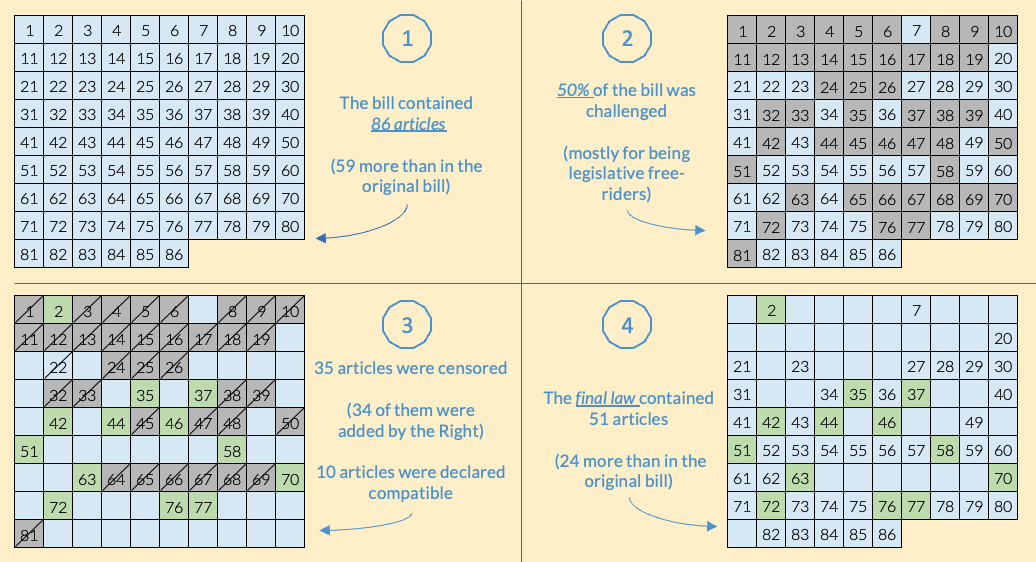

The outcome unfolded precisely as predicted. On January 25th, the Constitutional Council rendered its decision regarding the bill’s conformity to the Constitution. Out of the 86 articles, 47 were contested before the Court. A staggering 75% of the challenged content was deemed incompatible with the Constitution, resulting in 40% of the original bill being invalidated.

Figure 1 – Overview of the Constitutional Council’s decision on the immigration bill

Figure 1 – Overview of the Constitutional Council’s decision on the immigration bill

Notably, the immense majority of the censored content had been introduced by the right, with 34 out of 35 of their added articles struck down. In contrast, nearly all the government’s original proposal was upheld, with only 1 out of 27 facing rejection. The extensive censorship can be attributed to the mediocre quality of the bill submitted to the Constitutional Council. The Constitutional Council censored 32 articles for lacking a genuine connection with the law’s intended purpose (so-called “legislative free riders”). The hurried drafting process by the Houses’ Joint Committee certainly did not contribute to meeting the highest standards of legal drafting.

However, despite President Macron’s assertions, a total of 24 articles drafted by the Joint Committee were preserved, highlighting the significant influence of the right on the final version of the law.

Théo Fournier is a free-lance consultant in legal capacity building and executive training. He holds a PhD in comparative constitutional law from the European University Institute.

The views expressed in this blog post are the position of the author and not necessarily those of the Brexit Institute blog.

Image Credit: Ministère de l’Intérieur – www.interieur.gouv.fr, Licence Ouverte