Dr. Niall Moran (Assistant Professor, School of Law & Government, DCU. Brexit Institute Deputy Director, Dublin City University.)

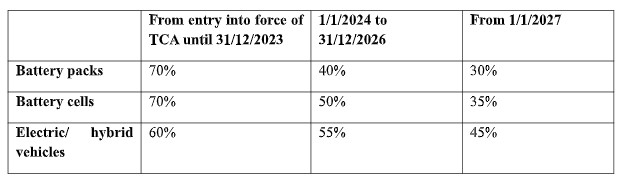

On 21 December 2023, the EU and the UK agreed to a three year extension to the Trade and Cooperation Agreement’s (TCA) rules of origin for electric vehicles (EVs) and batteries. This agreement was important for a number of reasons. Firstly, an extension to the transitional rules in this area was the simplest solution for avoiding the looming cliff edge and ten per cent tariffs that were due to kick in on 1 January 2024. Annex 5 of the TCA sets out changes to rules of origin (RoO) relevant to EVs that were due to be phased in from the end of 2023 to 2027. The extension essentially removed the third column, as illustrated in Table 1 below, with the values in column two remaining in place until 2027.

Table 1: Changes to the maximum value of non-originating materials for EV-related products under Annex 5, Section 2 of the TCA

The UK had been clear about its desire to maintain the transitional rules of phase one and this

stance was supported by industry. The Commission had stated that it had no intention of

revisiting these rules and the EU preference appears to have been for the UK to join the PEM

Convention.

The UK had been clear about its desire to maintain the transitional rules of phase one and this stance was supported by industry. The Commission had stated that it had no intention of revisiting these rules and the EU preference appears to have been for the UK to join the PEM Convention.

EVs are an emerging market that is unusually exposed to RoO as the price of the battery in an electric vehicle is a significant proportion of its overall value and at least 30% of its value. If this second phase had begun to apply in January 2024, the permissible level of non-originating materials for EVs and batteries would have decreased significantly. The changes that were due to come in would have served neither industry nor the parties to the TCA in any real sense, not to mention the contradictory message that would be sent by introducing tariffs for EVs but not internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles. Failure to reach an agreement would have been harmful to both EU and UK carmakers given the current shortage of battery production in Europe. The tariffs that would have resulted in this area would have resulted in significant trade diversion and billions in additional costs that would have mainly been passed on to the consumer.

Cumulation under the TCA

This question of RoO and the value of materials originating outside the parties has been the subject of considerable media coverage in relation to EVs. For a good to avail of preferential tariff treatment under a trade agreement, the good must originate in one of the parties to the trade agreement. There are a number of ways of calculating origin and ‘cumulation’ defines the extent to which inputs from other countries can be counted as originating in the producer’s country for the purpose of obtaining originating status and availing of preferential tariff treatment.

There are three main varieties of cumulation– full, diagonal and bilateral– in descending order of economic integration. Bilateral cumulation (the type provided for under the TCA) only allows producers to use materials originating in either the EU or the UK as if they originated in their own country. Diagonal and full cumulation allow for material inputs to goods from third countries with whom both parties have an FTA and operate the same rules of origin to be treated as originating in the country of the producer and thus to be eligible for preferential market access. Full cumulation is distinct from diagonal cumulation in that it allows the inclusion of inputs from any territory.

During TCA negotiations, the UK sought diagonal cumulation but EU rejected this. EU FTAs only provide for diagonal cumulation in respect of Pan-Euro-Mediterranean (PEM) Convention signatories. While the TCA only provides for bilateral cumulation, EU operates full cumulation across the European Economic Area (EEA) and diagonal cumulation for all contracting parties of the PEM Convention. This Convention includes 25 other countries in the Euro-Mediterranean region, ranging from Morocco to Israel, Georgia to Ukraine. Post-Brexit, the UK is no longer bound by the PEM Convention. This decision to only provide for limited cumulation will impact EU and UK industries that are particularly exposed to changes in rules on cumulation of origin.

Where to now? Options for amending the ‘new’ rules

This section considers the options for amending the TCA’s RoO in relation to EVs.

While the changes planned for 2027 may not necessarily serve either party, this does not mean a further extension should be expected. Such is the reality after Brexit and a consequence of the UK no longer being bound by the PEM Convention. Indeed, the current extension is complemented by a ‘lock-in mechanism’, “which ensures that the full regime for local content requirements…will apply as from 2027…[and] no changes will be possible before 2032”.

To date carmakers have tended to source these batteries from outside the EU or UK. China currently dominates global production of refined battery materials used in EV batteries. As per Table 1 above, the maximum value of non-originating materials for battery packs and battery cells is due to fall from 70% to 30% and 35% respectively at the start of 2027. The aim of this is to “gradually force” car producers to sources batteries locally. Consequently, if by 2027, EU and UK car producers cannot source batteries locally, their exports will face tariffs of 10% in the absence of a further EU-UK agreement in this area. The UK EV market is important for EU exporters and it is estimated that it will be worth close to €30 billion annually by the end of 2026 and the transition period. UK carmakers also export over 90% of their electric vehicles to the EU.

While the TCA was hailed as a trade agreement of “unprecedented ambition”, in this area at least, its terms will leave EU automakers behind their counterparts in Japan and other countries unless a deal is reached. EU exporters will face tariffs that will largely be avoided by Japanese carmakers, though differences in domestic battery production is the significant factor here.

While maintaining the current transitional rules provides a temporary solution for automakers, the question now arises as to the options for a longer term solution. There appears to be three options for reforming the TCA’s RoO beyond 2027:

1) allowing the final phase of the TCA to kick in whereby the permissible level of non-originating materials for EVs and batteries decreases significantly; 2) the UK joins the Pan-Euro-Mediterranean (PEM) Convention; or 3) an attempt to further extend rules whereby the level of non-originating materials remain at a higher level.

Option 1 is of course the default if no agreement can be reached. On the second option, the UK has not ruled out joining the PEM Convention with Minister for International Trade Ranil Jayawardena stating in November 2021 that “HM Government has not sought to accede to the PEM Convention at this time”. The primary issue with joining the PEM Convention is that it does not appear to solve the problem at hand. Even if the UK were to surmount the legal difficulties in joining the PEM Convention, China remains the primary source for refined chemicals. On option 3, the ‘lock-in mechanism’ makes the possibility of further changes to these rules before 2032 more difficult, though this may have to be re-examined at a later date.

If or when battery production takes place at scale in the EU or UK, the issue here will be greatly alleviated for EU-UK trade in EVs. While EU is wary of anything that resembles cakeism or cherry picking, the current extension is a good example of an area where EU-UK cooperation can occur and where flexibility can reap mutual benefits. Both sides have shown a willingness to listen to industry in certain areas and build on recent momentum in EU-UK relations.

In terms of the broader context, the drive to secure reliable access to critical raw materials is increasingly important to both the EU and the UK. Success here will be key to ensuring EU and UK automakers are able to compete in the EV industry and there is a strong case to be made for integrating EU and UK supply chains in this area. While the inclusion of the UK in European supply chains had been a given for decades, the reality of Boris Johnson’s Brexit deal is that there are now significant challenges for UK companies wishing to remain part of such arrangements.

The views expressed in this blog reflect the position of the author and not necessarily that of the Brexit Institute Blog.