Théo Fournier (European University Institute)

- Description of the electoral system

On Sunday, French citizens will vote in the second round of the elections for the National Assembly, the lower house of the French Parliament. Legislative elections are a major event in French politics. The National Assembly is indeed the lower house of the parliament: it votes the budget and has the final word on most of the legislation. Legislative elections also have a direct impact on French politics since the President of the Republic must appoint the Prime Minister according to the political make-up of the re-elected House.

The French executive, centralised around a directly elected President, relies on an alignment of the legislative majority and the presidential majority to function smoothly. With the support of a majority in the National Assembly, the President controls the initiative of bills, the amendment procedure, and their adoption. He is both a head of state and a head of government. Without the support of the National Assembly, the President is forced to appoint a Prime Minister from the opposition and loses at the same time many of his prerogatives to the Prime Minister.

However, the system is designed to favour the emergence of a presidential majority.

Voters elect the 577 députés – members of the National Assembly – in individual constituencies in a two-round majoritarian vote. In this system, a candidate is elected at the first round if they obtain more than 50% of the votes and their score represents more than 25% of the electorate. An election at the first round being unlikely (yet not impossible), a second-round of election takes place a week later. The two first candidates and any other candidate whose share of vote representing more than 12,5% of the electorate go through to the second round. Some second rounds can therefore gather three or even four candidates, especially in case of a high turnout.

The two-round majoritarian system creates a major discrepancy between the popular votes and the number of seats. In 2017, for example, Emmanuel Macron’s party – En Marche – gathered 49% of the votes but obtained an absolute majority of the seats (351 seats out of 577). The party winning the popular vote routinely gets a number of seats higher than its share of vote.

Since 2002, legislative elections take place right after the presidential elections. This reform was thought to favour the alignment of the legislative and the presidential majorities. Voters are indeed more inclined to confirm the results of the presidential elections and to give a majority in the National Assembly to the president. Candidates of the presidential majority benefit directly from the dynamic created by the election of the President as opposed to opposition candidates who are less likely to be considered a credible alternative. Why, vote for a party which just a few weeks ago lost the presidential election?

- Overview of the political campaign

The reform of 2002 reinforced political stability at the expense of politics. Since then, each freshly elected president has obtained an absolute majority of the house and could govern for five years almost without any opposition in the National Assembly. Consequently, legislative campaigns became secondary in French political life. The quasi-insurance of a victory of the presidential party made legislative campaigns quite predictable and even, frankly, boring.

The beginning of the 2022 campaign was no exception to the rule. Once Macron was re-elected, everyone was already commenting on the implementation of his programme, acknowledging that the legislative elections were a mere formality. Yet, the context of these elections was significantly different from the past ones.

As opposed to the 2017 elections, Emmanuel Macron was re-elected without much enthusiasm. He won mostly thanks to a rejection of Marine le Pen and the abstention of leftist votes. He did not manage to create a momentum around his presidential programme. Marine le Pen did not seem to want to take advantage of Macron’s difficult situation. She rather gave the impression of wanting to bypass the legislative elections. She rapidly stated that her party was not in any position to win the elections and that she would be satisfied if the Rassemblement National (RN) could merely increase its number of députés. Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who arrived third and very close to qualify for the second round, took advantage of the passive attitude of his two direct opponents. Freshly crowned new leader of the left, he launched his campaign around the motto “Mélenchon Prime Minister” in the days following the results of elections.

Mélenchon imposed himself as the main figure of the legislative campaign by managing to create an alliance of the left parties around his candidacy. This coalition, called the New Popular Alliance (NUPES), gathered Mélenchon’s party, La France Insoumise, the Socialist Party, the Greens, the Communists and a dozen more smaller parties. This alliance did not come without its own contradictions, for example on the attitude towards the European Union or on laïcité (secularism), but it remained all the same an historical event for the left.

Macron’s legislative campaign was far from being a success. In early May, En Marche secured a coalition – Ensemble – with three other political groups, two from the centre-right and one from the centre-left. Aside from that, Macron decided to shorten the campaign to its minimum by postponing the appointment of the new government until May 20, more than a month after his re-elections. He chose Elisabeth Borne, his former minister of Labour, as Prime Minister and decided that 16 out of the 23 ministers should run for the elections.

Macron failed to create momentum around the appointment of the government. The left alliance became progressively the central actor of the campaign to the point of leading the opinion polls two days before the first round.

- Interpretation of the results

The first round of the 2022 legislative elections was marked by a historically low turnout. Only 47% of the voters voted which is another proof of the growing disinterest of the French population for elections.

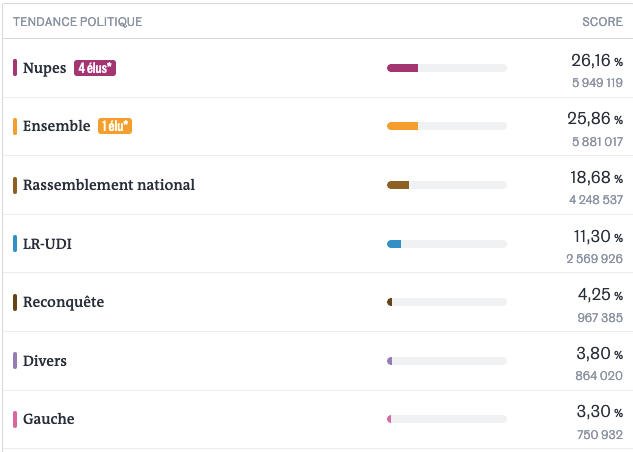

The first round produced the following results in terms of popular vote.

Figure 1: Results of the first round (popular vote) – source Le Monde

The main outcome is that Mélenchon won his bet. His NUPES coalition arrived first in terms of popular vote (26,16%) ahead of Macron’s Ensemble (25,86%) and Le Pen’s RN (18,68%). One should also note the strong score of the conservative’s LR-UDI (11,30%) despite a historical defeat at the presidential elections (their candidate won less than 5% of the votes).

However, a projection of the votes in terms of seats gives a completely different picture of the results.

Figure 2 : Seat projection – source: Le Monde

NUPES might have won the popular vote in the first round, but after the second round Ensemble will very likely be the majority party in the National Assembly with 255 to 290 seats as opposed to 150 to 190 for the left coalition. Mélenchon will not be Prime Minister and Macron should be free to choose his Prime Minister after Sunday. But why?

In a two-round majoritarian system, second-round runners can hope to gather the votes of the voters whose candidates didn’t qualify. These voters are more likely to choose a candidate who is closer to their ideals. They can also give their vote to one candidate to block the other. A left voter would then be inclined to vote NUPES by conviction or simply to block Ensemble. Similarly, a right voter would rather vote Ensemble by conviction or to block NUPES.

The NUPES is potentially the great loser of the transferable votes. Since it decided to aggregate the left-wing groups from the first round, its reserve of votes for the second round is very low. On the contrary, Ensemble could attract a large proportion of the voters who voted LR at the first round and who are faced with the choice between NUPES and Ensemble (which is the case in 271 constituencies).

Such a vote transfer is influenced by the practice of the so-called front républicain (republican front). The republican front is a long-established tradition to vote for a party or candidate opposed to the Rassemblement National. The republican front should benefit those Ensemble candidates who are in a dual with the RN (107 constituencies).

The republican front will be less likely to be successful in the 59 constituencies in which a NUPES candidate runs against a RN candidate. Right-leaning voters are indeed not as keen to vote for a left candidate to block the far right. It is even more the case if the left candidate is from the far left. In fact, the head of the conservatives LR decided to put on the same level the NUPES and the RN arguing that these two groups were both extreme and incompatible with French republican values. Regrettably, some members of Ensemble, including ministers, defend a similar stand, forgetting that Macron himself was elected by a republican front in April.

*

On Sunday, Ensemble will probably get more seats than any other party. The question is whether Ensemble will get an outright majority or merely a plurality, and if it is a plurality, will Ensemble be looking at its right or at its left to form a coalition?

In any case, the presidential party will not get an outright majority on its own as was the case in 2017. It will need the support of its coalition partners of Ensemble to be majoritarian. This is already a massive a blow for Macron: since 2012 the National Assembly had always been dominated by the President’s party. And never since the 1960s had the far-left been the main group of opposition.

There are some interesting times ahead for French politics!

Théo Fournier holds a PhD in law from the European University Institute. He is a 2021/2022 reconstitution fellow (reconstitution.eu) and a bar-trainee at the Paris Bar School.

The views expressed in this blog reflect the position of the author and not necessarily that of the Brexit Institute Blog.

Image Credit: “Palais Bourbon – National Assembly of France” by ell brown is licensed under CC BY 2.0.