Professor John Doyle (DCU)

The results of the Northern Ireland Assembly election, which have seen Sinn Féin become the most popular party in Northern Ireland, with the right to nominate the First Minister, are truly historic. The boundaries of Northern Ireland were defined 101 years ago, in an attempt to ensure a permanent unionist majority. The potential election of a Sinn Féin First Minister is a deeply symbolic event – a clear statement that the equality promised in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement is changing Northern Ireland, and a reflection of political and demographic change.

On Brexit and the Protocol, at least 53 of the 90 members of the new Assembly will vote to confirm the Protocol’s arrangements, if the alternative is either a hard border on the island of Ireland or a ‘no deal’ Brexit. This is an increase of 3 compared to the last Assembly.

The election result also reflects growing support among both Irish nationalist voters and some parts of the political centre ground, for the creation of a united Ireland inside the European Union, as the European Council has already agreed that Northern Ireland would automatically be inside the EU if it becomes part of a united Ireland, following the German precedent.

The Results

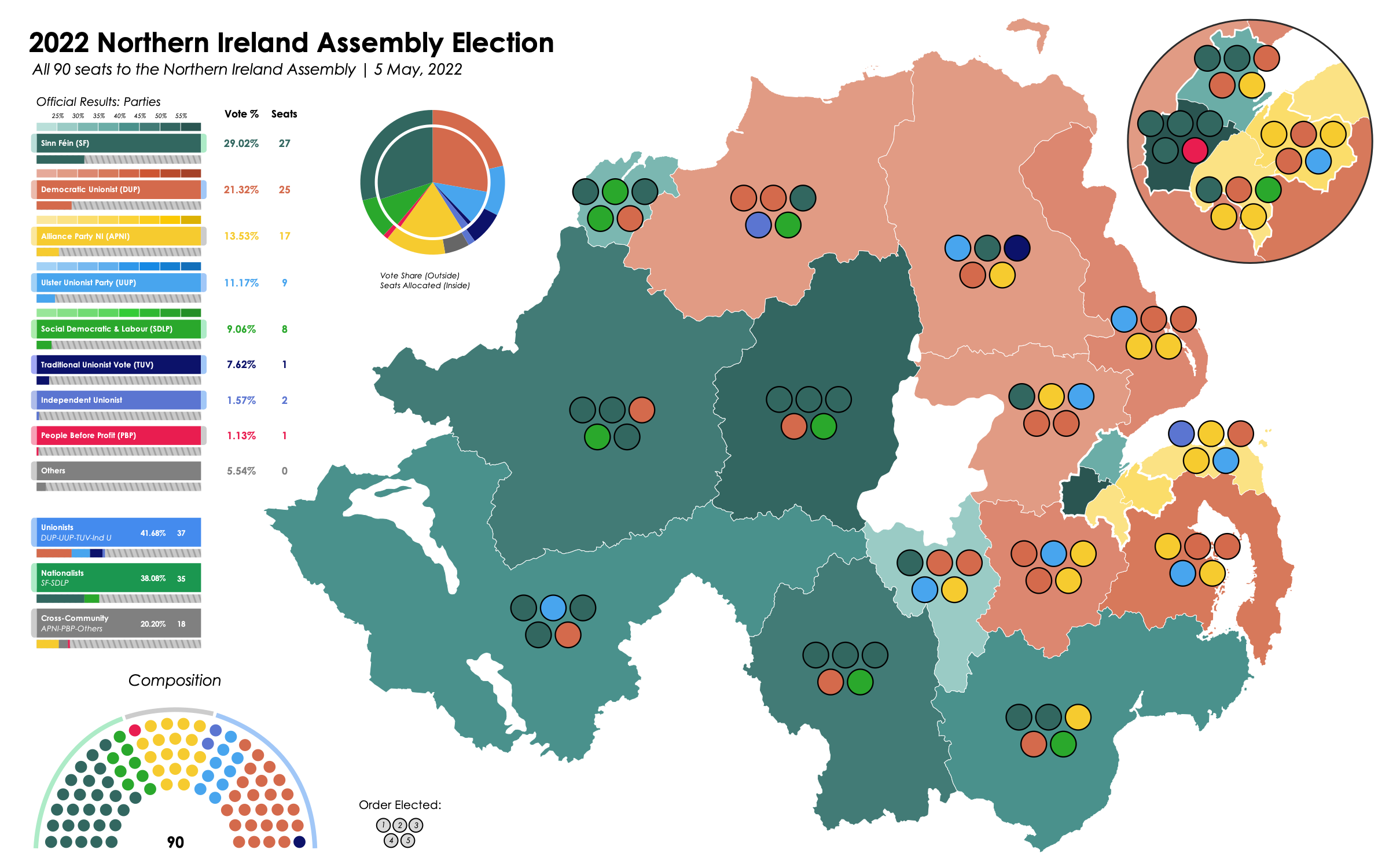

Sinn Féin went into this election with some of the most marginal seats in Northern Ireland after a strong 2017 performance. A new party Aontú, formed by a former Sinn Féin TD Peadar Tobin who was suspended from the party for voting against liberalisation of abortion legislation in the South, sought to attract more conservative supporters, while other small parties challenged Sinn Féin from their left. In the end, despite some minor fracturing of the first preference vote, Sinn Féin increased their support by 1%, to 29%, comfortably held all of their marginal seats, challenged for others, and lost an extra seat in South Down by not running a third candidate. Lucid Talk’s final opinion poll (which underestimated the SF vote by 3%) indicated that 38% of 18-to-24 year olds across all of Northern Ireland, intended to vote Sinn Féin (which would be over 40% if the underestimate was evenly spread). The nationalist community was very exercised by the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) position that a nationalist should not be First Minister. Sinn Féin will therefore look to a future election with confidence.

The centre ground Alliance Party increased their first preference vote share by 4.5%, to 13.5%, and increased their number of seats from 8 to 17, due their very strong performance in attracting transfers under the PR STV system used for the Assembly. Alliance dominated the centre, taking the Green Party’s only two seats and winning seats from the nationalist SDLP and both unionist parties.

In contrast, despite a high-profile campaign against the ‘Protocol’ and against the idea of a Sinn Féin First Minister, this was a disaster for the DUP, their worst result since 1998. The decline of 6.7% in their vote share, was greater than the increase for the more hard-line, Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV), indicating a wider loss of support. The Ulster Unionist Party lost one seat but on balance they held their own in difficult circumstances. The TUV, polled 7.6% but only managed to win one seat as they attracted almost no lower order preferences.

It was also a very poor result for the moderate nationalist SDLP, whose vote share dropped by almost 3%, and who lost 4 of their 12 seats including that of their Deputy leader. Their vote has dropped in seven Assembly elections in a row, from 22% in 1998, to 9%. In addition to long-term trends, the high-profile opposition of some candidates to any liberalisation of abortion law, was deeply unpopular among young and liberal voters. One poll had the SDLP at 2% among voters aged 18 to 24.

Looking at the longer-term trend data within political blocs, this was the lowest percentage vote total by unionists since the modern Assembly was established in 1998. Whereas over 51% of voters supported unionist parties or independents in 2003, this has now dropped to 42.2%. In contrast, the proportion of people supporting parties or independents who support a united Ireland has remained quite constant, being 41.7% in this election. This 0.5% difference between supporters of a united Ireland and unionists – is the smallest gap in the modern era.

The political centre ground has grown over the past 25 years, from about 9% to 16% and this growth is across all age groups – most pronounced in older voters. The centre is now dominated by the Alliance Party, whose party leader Naomi Long has succeeded in positioning the party as one which supports the Good Friday Agreement, and which does not promote a specific position for or against a united Ireland. Opinion poll evidence suggests this public neutrality is reflected in their voters – who are split three ways – over one third supporting a united Ireland, one third supporting Northern Ireland within the UK, and one third undecided on the issue.

The growth of the centre did not benefit the Greens who lost their two seats. There were reports at constituency level that grassroots members who opposed the party entering government in the Republic had not been active in the campaign.

Impact on a United Ireland

The election result will have no immediate impact on the holding of a referendum on Irish unity. Under the terms of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement the power to hold a referendum is held by the British Government. Even Sinn Féin is not calling for an immediate referendum. What they are seeking is the commencement of formal planning and public debate on what a united Ireland would involve, in areas such as health, pensions, the economy and how minorities, new and old would be guaranteed equal rights. There will be increased pressure now to begin that planning, and if Sinn Féin also lead the Irish government after the next general election in the Republic, which polls suggest they will, then formal government planning for a referendum will certainly begin.

Forming a Power-Sharing Executive

Within Northern Ireland, it is unlikely that a power-sharing executive will be immediately formed. The DUP have refused to clarify their attitude to sharing power with a Sinn Féin First Minister, and as the largest unionist party if they refuse to nominate a Deputy First Minister – who in fact has equal power – then legally an Executive cannot be formed, and power will return to London. The Northern Ireland Assembly is however very popular in Northern Ireland in all communities. People like having political decisions made locally, and there will be pressure on the DUP in the weeks ahead to re-enter power-sharing. Already the British, Irish and US governments have publicly called on them to form an Executive.

The DUP have said they will not form an Executive unless the Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland, agreed between the British Government and the European Union is scrapped. The problem facing the DUP is that the incoming Assembly is even more supportive of the Protocol than the out-going Assembly, and all nationalist and centre ground Assembly members oppose any unilateral move by the British Government on this issue. Legally the DUP can prevent a power-sharing executive from being formed. Politically however a long stalemate followed by a new election in the autumn, is very likely to see their support decline again, further alienate Irish nationalists, and may also increase support for a referendum on Irish unity among the middle ground, as a route for Northern Ireland to re-join the European Union.

Professor John Doyle is Director of Dublin City University’s Institute for International Conflict Resolution. He has published widely on Northern Ireland, mostly recently with a significant focus on the impacts of Brexit on the peace process there. John is leading the University’s contribution to cross-border collaboration on the island of Ireland, including Ireland North-South: a research programme on the Future of the island of Ireland, exploring the research which needs to be conducted and debated before a referendum on a United Ireland is held.

The views expressed in this blog reflect the position of the author and not necessarily that of the Brexit Institute Blog.

Image Credit: By Talleyrand6 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=116892066