John Cotter (Keele University)

The 10th April will mark the twenty-second anniversary of the signing of the Good Friday Agreement. The contemporary public health crisis aside, it is quite likely that the Agreement would have received less attention this year than it has in the past four years. Throughout the fraught period in which the Brexit withdrawal negotiations were being conducted, there appeared a serious risk to the survival of the Good Friday Agreement that gave it extra currency. For a long time, the British government maintained a position that the UK leaving the Customs Union and EU Internal Market, which appeared to be the UK government’s most pressing priority, need not lead to the imposition of a hard border on the island of Ireland. The Chief Constable of the Police Service of Northern Ireland, among others, warned that a hard border would risk a return to the violence that the Good Friday Agreement had been designed to end. Ultimately, the threat of the immediate imposition of a hard border on the date of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU was avoided by the conclusion and ratification of the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement of the 17th October 2019. Moreover, the Northern Ireland Protocol, forming part of the Withdrawal Agreement, sought to facilitate the seemingly contradictory British aims of leaving the Customs Union and Internal Market while at the same time preventing a hard border, by effectively maintaining Northern Ireland’s participation in the Customs Union and significant elements of the Internal Market, subject to periodic votes of consent by the Northern Ireland Assembly.

With the immediate threat to the Good Friday Agreement averted and an arrangement in place to ensure its continued survival, it might be attractive to consider the Brexit chapter closed, and the Agreement safe from the dynamics of Brexit. I would suggest that such a view would be naïve. Conservative-Party slogans notwithstanding, Brexit is not done. Like peace in Northern Ireland, it is a process. And like the Good Friday Agreement, the Withdrawal Agreement (including its protocols) may be seen as an instrument to allow the parties involved in the process a mutually-agreed legal space within which their interests can be advanced. Both Agreements leave questions of considerable import ultimately unresolved. The Good Friday Agreement acknowledges that the constitutional position of Northern Ireland is not fixed and could change as the result of democratic exercises. The Withdrawal Agreement, by virtue of the constraints imposed by Article 50 TEU, facilitates the withdrawal of the UK from the EU and takes account of the future relationship between those entities, but it does not determine the nature of that future relationship, which remains to be negotiated. Even if agreement on this future relationship is concluded between the EU and the UK, the process continues in the performance (or lack thereof) of the terms of such agreement and of the Withdrawal Agreement itself. In the specific context of Northern Ireland, the status quo provided for in the Northern Ireland Protocol is, as mentioned above, subject to the periodic consent of the Northern Ireland Assembly, and could therefore be ended. A refusal by the Northern Ireland Assembly to provide such consent would reintroduce the danger of a hard border, and the consequential risks that would pose to the functioning of the Good Friday Agreement. While the possibility of the Assembly withholding its consent might appear remote at present, it is nevertheless there.

Another conceivable threat that remains to the Good Friday Agreement is the possibility of infringement of the Northern Ireland Protocol or, more charitably, differing understandings of what the Protocol means in practice. Boris Johnson and Brandon Lewis, the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, have both claimed that there would be no checks on goods crossing the Irish Sea after the Brexit transition period. An absence of such checks would clearly constitute an infringement of the UK’s obligations under the Northern Ireland Protocol. While there are legal remedies provided both in the Withdrawal Agreement itself and in international law more generally for infringements of the Protocol, such forms of redress carry with them the familiar weaknesses of international legal remedies in terms of coercive force and might also be of limited practical assistance were the UK unperturbed by the economic and political consequences of non-compliance. Those consequences, in addition to their impact on Northern Ireland, would, of course, be grave: not least in posing a threat to the UK’s chances of concluding a trade agreement with the United States.

It is not my intention to imply that the probability of risk to the Good Friday Agreement, specifically the materialisation of a hard border, posed by continuing Brexit dynamics is high. The disincentives on all sides are significant. The take-home message is simple: Brexit is not done and the Northern Ireland Protocol does not provide a permanent guarantee against a hard border, neither in law nor in fact. The EU’s institutions and the Irish government will need to remain vigilant and as committed on a continuing basis to the protection of the Good Friday Agreement as they were during the Article 50 TEU process. To conclude on a cliché: “The price of peace is eternal vigilance.”

The views expressed in this blog reflect the position of the author and not necessarily that of the Brexit Institute Blog

John Cotter is a lecturer in law at the School of Law, Keele University

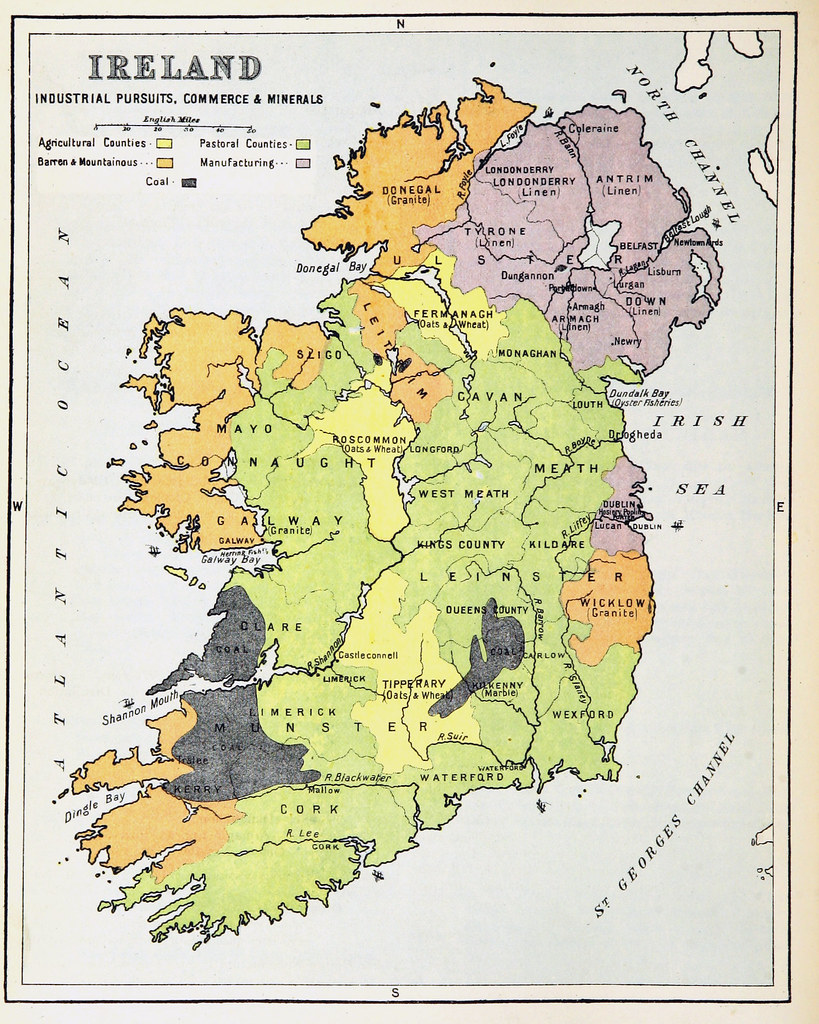

Image credit: “Ireland” by sjrankin is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0