Feargal Cochrane* (University of Kent)

Enoch Powell, the former Ulster Unionist Party MP for South Down, once famously remarked that ‘all political careers end in failure’. In view of recent events within the leadership of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), he could have added, that some also end in disgrace and humiliation, as his former protégé Sir Jeffrey Donaldson seems to have catapulted spectacularly from hero to zero in a matter of weeks.

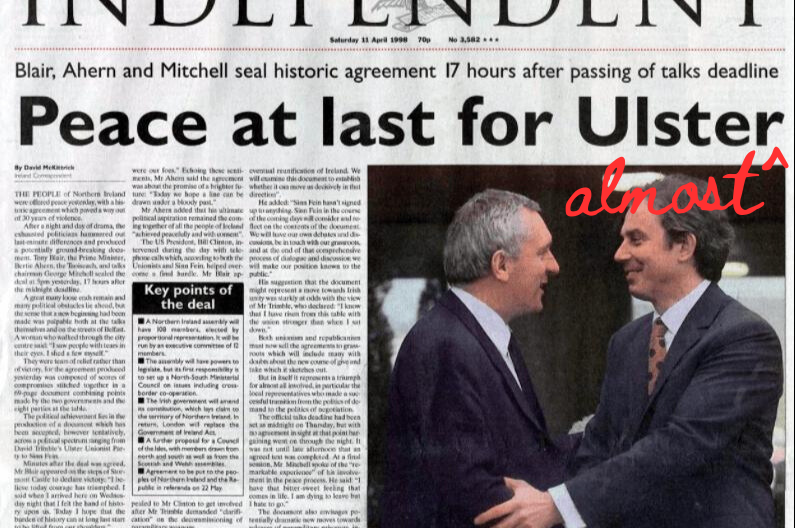

26 Good Fridays after walking out of the final session of the All-Party Talks that resulted in the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement in 1998, Donaldson walked into a police station, where he was charged with serious sexual offences of a historical nature. From Good Friday Agreement to Good Friday Arraignment, was the verdict of some social media commentators on the events of this year’s tumultuous Good Friday. He resigned as party leader, deleted his social media accounts and has also had his party and Orange Order membership suspended.

It all looked a lot rosier for Donaldson and his party a few weeks ago. Having spent most of his time since being elected leader of the DUP defending his party’s boycott of the devolved institutions in Northern Ireland, Donaldson finally led his party back into government in February. In doing so he deftly side-stepped those within his party opposed to the restoration of power-sharing, while his ministerial picks and nomination of Emma Little-Pengelly as deputy First Minister, demonstrated an assured political touch. The first two months of the restored Executive and Assembly have gone well, with ministers tackling their new portfolios with energy as well as some much needed sensitivity.

The first ever nationalist First Minister, Michelle O’Neill, and first ever unionist deputy First Minister, Emma Little-Pengelly, have also acquitted themselves admirably to date, showing a united front on several occasions when it would have been easier not to do so. The hard politics of agreeing a joint Programme for Government and delivering it within a tight fiscal environment will remain a challenge for the rest of the parliamentary mandate and those smiles may yet turn into rictus grins before the summer is out.

But for now, it’s a case of so far, so good, and the DUP has re-entered power-sharing giving the impression that it means it this time. Donaldson’s leadership has been crucial to this shift away from the traditional DUP refrain of ‘Ulster Says No’ to a more pragmatic and progressive commitment to power-sharing. Those within the DUP who remain adamant that the post Brexit trade border in the Irish Sea is still a real and present danger to the Union were noticeably content to blame the UK government, rather than Donaldson, after the unveiling of the UK Command Paper Safeguarding the Union in January. Unionist opponents outside the DUP have looked increasingly shrill and isolated –their cries of betrayal echoing back into their social media accounts with diminishing returns. Their public meetings are modest in size (Orange halls rather than concert arenas) and have led to little by way of a coherent strategy that offers unionists a realistic alternative. The initial whispers of civil disobedience and street protests meanwhile, have disintegrated as fast as former SDLP leader John Hume’s famous ‘two balls of roasted snow’.

After the Donaldson bombshell landed on his party and the rest of Northern Ireland at the end of March, the DUP moved swiftly to fill the vacuum left by his resignation. The appointment of Gavin Robinson, as Interim Leader suggests continuity in policy terms. Robinson is known as a pragmatist and he has moved quickly to try to calm political nerves. There is little talk of any strategic re-evaluation, at least for the moment, and if Robinson is confirmed in the job he is likely to want to persevere with the current approach, not least because he was one of the main architects of the deal with the UK government that led to the DUP ending its boycott of the devolved institutions. While that deal was fronted by Sir Jeffrey Donaldson, the vast majority of DUP MLAs support the return to government and the restoration of their full duties (and full salaries) that go with that. The DUP MPs at Westminster meanwhile seem to have little appetite to contest the direction of travel that has been set.

The political fallout from all of this will take some time to become clear, but the Westminster General Election is just around the corner and will be the first electoral test for the DUP in the post-Donaldson era. Will DUP voters reward the party for finally returning to Stormont and ending the political stalemate that has blighted Northern Ireland for the last two years? Or will they vote for other parties, such as Jim Allister’s more radical Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV), which announced an electoral pact with Reform UK in March. The TUV has consistently argued that the DUP has reneged on its initial opposition to the Windsor Framework deal and betrayed its voters. More liberal unionists may on the other hand transfer their vote to the UUP or even to the ascendant Alliance Party which is broadly agnostic on the constitutional question and has campaigned energetically for reform of the devolved institutions to increase their effectiveness. Or, will unionist voters demonstrate their exasperation at the apparent inability of their leaders to demonstrate that Northern Ireland can work politically by just staying at home at the next election? Some of these questions will be answered in the months ahead when the General Election finally takes place. For the moment it looks like the Good Friday Agreement will reach its 27th birthday next year and that its model of devolved power-sharing will remain the main political axis in Northern Ireland.

Of course who knows what else might happen in the meantime?

The views expressed in this blog post are the position of the author and not necessarily those of the Brexit Institute blog.