Stefan Telle (European University Institute)

On this Europe Day (May 9), it is worthwhile to reflect on the fact that seven years have passed since the British membership referendum of 23 June 2016. At that time, few had anticipated the outcome. But with 52% of British voter preferring exit over voice, for the first time a member state was now set to leave the European Union (EU). It was a moment of existential crisis. There was widespread fear that the EU would not be able to rise to the challenge, and that other member states may follow the British example.

Today, hardened by three years of global pandemic, a major ongoing war of aggression in Ukraine, spiking costs of living, and equipped with the benefit of hindsight, one may be forgiven for dismissing Brexit as just another issue. The EU was always going to fare well in the negotiations. The UK was always going to descend into political chaos and economic decline. However, it is important to remember the context in which Brexit started to unfold in 2016. In the UK, the Conservative Party enjoyed an outright majority in parliament. By contrast, the EU had just emerged from the divisive euro- and refugee-crises. Eurosceptic populism was going from strength to strength in the member states. Across the Atlantic, Donald Trump was elected president of the United States in November 2016. “F… you 2016” was a viral meme.

In that context, Ivan Krastev was certainly not alone when he argued that “[i]f the disintegration of the EU was only recently considered unthinkable, after Brexit it seems (in the eyes of many) almost inevitable.”[1] But that is not what happened. Instead, the EU mustered a united and effective response to Brexit. Today, no one is talking about exit any longer. In fact, while the EU’s responses to the eurozone and migration crises were divisive and lacklustre, its responses to Covid-19 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine were unexpectedly decisive. From that perspective, Brexit was a turning point in EU crisis-management.

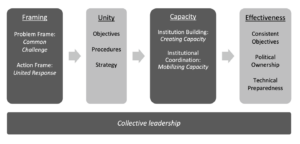

How did the EU pull this off? In our recent book The EU’s Response to Brexit: United and Effective, Brigid Laffan and I argue that the EU was “united and effective” in Brexit because it got the process right. In focussing on the procedural aspects of the EU’s Brexit response, we do not dispute that the size of the Single Market put the EU in a strong bargaining position[2]. What we highlight, however, is the agency of politicians and bureaucrats in defining common objectives, in maintaining broad ownership, and in building negotiating capacity (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1 Explaining the EU’s united and effective response to Brexit.

Source: Laffan and Telle (2023) The EU’s Response to Brexit. United and Effective. Palgrave Macmillan, p. 17.

We argue that the discursive framing of Brexit as a “common challenge” which required a “united response” was a crucial precondition for achieving internal agreement on negotiation objectives, procedures, and strategy. That framing was immediately disseminated by the EU institutions in a joint statement in the early hours of 24 June 2016; and it was endorsed by the member states at an informal meeting on 29 June 2016. In terms of objectives, the EU underlined that any agreement with the UK “will have to be based on a balance of rights and obligations” and specified that “[a]ccess to the Single Market requires acceptance of all four freedoms.” In terms of procedure, the EU insisted that “[t]here can be no negotiations of any kind” before the UK had notified the EU about its intention to leave. Moreover, an agreement on future relations would “be concluded with the UK as a third country”, meaning that a divorce settlement would have to precede negotiations about the future. In terms of broader strategy, the emphasis was put on the necessity “to remain united”, stressing that the EU would remain the central framework “to deal with the challenges of the 21st century.” These central tenets were further fleshed out and codified in the negotiating guidelines of April 2017. Throughout the negotiations, they were never seriously challenged.

Discursive unity was central to building up the EU’s collective capacity for handling Brexit. It reined in inter-institutional competition and stimulated a dynamic of institutional coordination. In late 2016, the EU agreed on clear procedural arrangements for the conduct of the negotiations. Moreover, a dedicated “institutional ecology” for handling Brexit was emerging with the Council’s Working Group, the Commission’s Task Force, and the Parliament’s Steering Group. These de novo bodies served to insulate the EU’s daily functioning from the Brexit negotiations. At the same time, they ensured that the interests of the member states, citizens, and the Union equally shaped the EU’s response to Brexit. Transparency and continuous engagement became the central practice norms among these institutions. In that way, they helped mobilise and direct technical expertise towards mustering a united and effective response to Brexit. When the negotiations finally began in June 2017, the EU knew what it wanted, had brought everyone on board, and was well prepared on a technical level.

We submit that these resources enabled the EU to remain steadfast and united over the next four years of increasingly acrimonious negotiations with the UK. The UK had adopted a confrontational course from the outset, and gradually cranked up the brinkmanship as the negotiations unfolded. An explanation for this approach lies in the Conservative Party’s loss of its outright parliamentary majority in June 2017. The resulting dependence of the Conservative Party on the votes of the Northern Irish DUP considerably shrank the UK’s ability to agree to compromise solutions with the EU. With little of substance to offer, the successive governments of Theresa May and Boris Johnson tried to force concessions from the EU by steering the negotiations to the brink of failure in the hope that the EU would cave and prefer a better deal for the UK to no deal at all. That strategy failed because the EU internally agreed that no deal was better than an unbalanced deal. In addition, it expertly utilised its superior technical negotiation capabilities to shepherd the negotiations towards a balanced negotiated outcome, its overarching goal.

In sum, the EU’s response to Brexit shows under which conditions and through what procedures the EU can act in a united and effective fashion in response to an existential crisis. The EU has been criticised for showing little strategic foresight in the negotiations. In that view, the EU’s unrelenting stance was responsible for the acrimonious post-Brexit relationship at the time when neither party could well afford it. That argument is misleading and, in hindsight, seems unfounded. Brexit was the choice of British voters. Calling early elections just before the negotiations began was Theresa May’s choice. Being pro-Brexit but anti-border was a DUP choice. Adopting a madman strategy to the negotiations when nothing else worked was Boris Johnson’s choice.

The EU did not want Brexit. But from the outset, its objective was to protect the collective. In hindsight, this seems to have been exactly the right approach. While EU-UK relations remained abysmal under Prime Minister Boris Johnson, they have considerably improved under his successor, Rishi Sunak. The Windsor Framework of February 2023 addresses dispute over the Irish Protocol and provides a basis for rebuilding a positive relationship. Geopolitically, the UK and the EU are on the same side in responding to Russia’s War against Ukraine. And as British citizens increasingly get to experience the economic fallout from Brexit, a stable majority now thinks that it was wrong to leave. And while the spectre of disintegration haunted the EU in 2016, today the focus is on further enlargement.

Stefan Telle is co-author, with Prof Brigid Laffan, of the The EU’s Response to Brexit: United and Effective (Palgrave, 2023). He has been a Research Associate at the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute in Florence. In the Horizon 2020 project “InDivEU – Integrating Diversity in the European Union”, he studied the preferences of EU member state governments concerning differentiated integration. Earlier, Stefan was a Leibniz Fellow at Leipzig University (2019) and a visiting lecturer at the University of Yangon in Myanmar (2017/2018). He completed his PhD studies in the Marie Curie ITN “RegPol2 – Socio-economic and Political Responses to Regional Polarisation in Central and Eastern Europe” (2017).

[1] Krastev, I. (2017) After Europe. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, p. 108.

[2] See Schimmelfennig, F. (2018) ‘Brexit: differentiated disintegration in the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25, 8, pp. 1154-1173.

The views expressed in this blog reflect the position of the author and not necessarily that of the Brexit Institute Blog.