Jasmine Faudone (Dublin City University)

On 27 February 2023, the President of the European Commission, Ursula Von Der Leyen, and the British Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, announced an agreement on the Northern Ireland Protocol: the Windsor Framework. On the one hand, the adoption of the Windsor Framework was positively welcomed as it represents a break of the political stalemate surrounding the Northern Ireland Protocol. However, on the other hand, its main development, the so-called Stormont Brake, caused debate as to its effectiveness.

The Stormont Brake will enable members of the devolved Northern Ireland Assembly (which meets at Stormont) to initiate a procedure that could delay or even block the entry into force of EU Single Market rules in Northern Ireland. Its purpose is to alleviate the perceived “democratic deficit” in Northern Ireland, wherein the territory is subject to EU rules without having a democratic input into the making of those rules. The inclusion of the Stormont Brake in the Windsor Framework was intended to entice the political parties in Northern Ireland – and in particular the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) – to restore the Stormont Assembly and the Northern Ireland executive, which are currently suspended.

This short commentary reports on the main novelties of the Stormont Brake compared to Art. 13 of the Northern Ireland Protocol, highlighting its main legal issues.

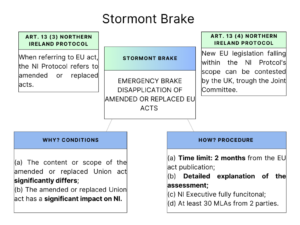

Article 13 (3) of the Northern Ireland (NI) Protocol states that ‘when this Protocol refers to a European Union act, that reference shall be read as referring to that European Union act as amended or replaced’.[1] Article 13 (4) of the NI Protocol refers to the adoption of new legislation by the EU.[2] In that case, the Union shall inform the UK of the adoption of such new legislation within the Joint Committee. The parties can request to have an exchange of views within the Joint Committee, within 6 weeks of its adoption.[3] The new Stormont Brake, in fact, adds an exception to Article 13 (3) of the NI Protocol. The United Kingdom may block the application of an amended or replaced European Union act by notifying the Joint Committee that it has activated the procedure. It is therefore an emergency measure, and triggers a suspension of the application of the amended or replaced EU act. However, the procedure’s initiation requires compliance with certain criteria, both substantive and formal. First of all, the United Kingdom has to meet the two months deadline – from the publication of the act – to notify the Joint Committee. Second, the notification must be accompanied by a detailed substantial and procedural explanation. In other words, the UK must make clear the reason behind the procedure’s activation, how the assessment was conducted, and the steps followed to trigger the Stormont Brake. The EU representatives sitting in the Joint Committee can request further explanation within two weeks.

Why? And How? Conditions and procedure to trigger the Stormont Brake

What is the rationale behind this emergency measure? The image below represents the dual path that is available. Indeed, the Stormont Brake can be activated if:

(a) the content or scope of the European Union act as amended or replaced by the specific European Union act significantly differs, in whole or in part, from the content or scope of the European Union act as applicable before being amended or replaced; and

(b) the application in Northern Ireland of the European Union act as amended or replaced by the specific European Union act, or of the relevant part thereof as the case may be, would have a significant impact specific to everyday life of communities in Northern Ireland in a way that is liable to persist.

The Stormont Brake can be activated if the conditions (a) and (b) met, but only in relation to the part of the European Union act amended or replaced interested by (a) and (b), meaning that the rest of the European Union act shall apply. The procedure is activated within the Joint Committee with a number of additional conditions. The mechanism can be activated only if the NI Executive is fully functional. The Executive should be in place, with a First Minister (FM) and a Deputy First Minister in regular session. Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) should act in good faith, including in the appointment of the FM. The minimum threshold is an activation by thirty MLAs (out of a total of ninety in the Assembly) from at least two parties (excluding speakers and deputy speakers). They have to demonstrate that they considered other options prior such activation, including the consultation of the social parties.

At this point, the NI Assembly notifies the UK, which then notifies the EU.

Main Legal Issues

As noted above, the main legal issues for applying the Stormont Brake are related to both its scope of application and its procedure. In terms of scope of application, the Stormont Brake refers to amended or replaced European Union acts. Article 13 (4) of the NI Protocol, on the other hand, refers to new EU legislation. Moreover, Art. 13 (4) NI Protocol establishes that the UK can object to new EU legislation falling within the NI Protocol scope for any reason – meaning without any impact assessment on Northern Irish communities, in contrast with the Stormont Brake provision. The issue is therefore to distinguish what is new and what is amended or replaced. Furthermore, the main legal issues will surely arise from the grey area: for example, how to consider European legislation that is primarily new but only amends some provisions of existing legislation? Moreover, it is not clear what ‘significant impact on the Northern Irish communities’ means.

Finally, in terms of procedure, the Stormont Brake raises concerns about its actual applicability. Even though the time limit – two months after the adoption of the EU act to activate the procedure – seems reasonable, the requirements related to the NI Executive and to the Members of the NI Legislative Assembly might be difficult to meet. Those criteria imply political stability and the perfect functioning of the power sharing mechanism established by the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement, factors that have faltered in Northern Ireland precisely because of Brexit

In conclusion, these issues lead to questioning the effectiveness of Stormont Brake. On the one hand, the Stormont Brake certainly represented a break in the political stalemate surrounding the NI Protocol but, on the other hand, it remains to be seen how it can pass the test of practical implementation, and any future political storms.

[1] Art. 13 (3) Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland, Common Provisions. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2020.029.01.0007.01.ENG&toc=OJ:L:2020:029:TOC (last access 22 March 2023).

[2] Idem.

[3] Art. 13 (4) Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland: ‘Where the Union adopts a new act that falls within the scope of this Protocol, but which neither amends nor replaces a Union act listed in the Annexes to this Protocol, the Union shall inform the United Kingdom of the adoption of that act in the Joint Committee. Upon the request of the Union or the United Kingdom, the Joint Committee shall hold an exchange of views on the implications of the newly adopted act for the proper functioning of this Protocol, within 6 weeks after the request’. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2020.029.01.0007.01.ENG&toc=OJ:L:2020:029:TOC (last access 22 March 2023).

Photo Credit: BBC

The views expressed in this blog reflect the position of the author and not necessarily that of the Brexit Institute Blog.