Feargal Cochrane (University of Kent)

In the television action series 24, every season was comprised of 24 episodes, each one a consecutive hour of a crisis, when the flawed hero, counter-terrorist agent Jack Bauer, tried to stop the bad guys and save the day. Sometimes his methods were questionable, the multiple plot lines could be confusing – and at times it was difficult to tell whether he was making any progress at all or just making things worse.

As of 10 April 2022, Northern Ireland has its own spin off version of 24, but instead of the season comprising 24 consecutive hours, it has been 24 consecutive years since the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement (GFA) was concluded. So nigh on a quarter of a century later, the key question remains whether the agreement reached on 10 April 1998 has produced political institutions with the capacity to lead Northern Ireland out of violent political conflict into a more stable, prosperous and harmonious future?

It is easier to be sceptical than it is to be optimistic, given that the institutions have been suspended for almost 40% of the time they have existed over the last 24 years. When the devolved institutions have managed to function, they have been defined as much by their inadequacy as by their record of effective governance. Clearly these institutions have brought a measure of stability to Northern Ireland but they have been chronically dysfunctional and endemically brittle over the period. Successive mandates have come and gone since the institutions were first established in 1999 but all have lacked the capacity to tackle sectarianism and community division, or to deal effectively with the legacy of political violence.

While the devolved institutions were having enough problems prior to 2016, the Brexit referendum of that year undoubtedly complicated political relationships in Northern Ireland in ways not envisaged when the GFA was negotiated. The less than elegant process of Britain negotiating its way out of the European Union since 2016 has only served to make the institutions more brittle and to demonstrate Northern Ireland’s vulnerability to external events over which it had little or no control.

This might all seem a bit pessimistic, but there is another side to the coin. Building peace is a painfully slow and frustrating process everywhere and Northern Ireland is not unique in that respect. The society has changed hugely since 1998 and the GFA itself has evolved and is likely to continue to do so. Aside from external drivers like Brexit, the devolved institutions have now developed a capacity for an official opposition, thanks in large measure to the efforts of former UUP Deputy Leader John McCallister, something not envisaged when the institutions were first established in 1999. The second wave of devolved government after the institutions were restored in 2007 saw the introduction of a Justice Minister as well as the devolution of policing and justice to Northern Ireland following the Hillsborough Castle Agreement in 2010. Further changes are likely as Northern Ireland’s political demography evolves, not least a move to Joint First Ministers to reflect the reality that it is a shared and interdependent role with equal responsibility. While up to now it has suited unionists to make this a political virility test, maximising voter turnout at the prospect of a Sinn Fein First Minister, it is more likely they will see the attractions of a move to Joint First Ministers when they can no longer rely on being the largest party in the Assembly.

It is also likely over the medium term that the structures of the GFA will have to evolve further to incorporate the growing group of non-aligned voters in Northern Ireland. Those who see themselves as being both British and Irish, or neither, and the sustained growth of the Alliance Party vote over successive elections, likely to be underlined on 5 May, is increasingly exposing a democratic anomaly in the 1998 Agreement.

Proportionality lies at the heart of the power-sharing system in Northern Ireland in order to ensure that there can be cross community support for important decisions. To determine this it has been deemed necessary for those elected to the Northern Ireland Assembly to ‘designate’ themselves as being either a unionist or a nationalist – though it was also possible to opt out into an ‘other’ category. This remains a functional but crude mechanism to facilitate a system of cross community votes and safeguards within the political institutions. The ‘others’ were the awkward residue, anticipated in 1998 to be small in number and peripheral to the key unionist-nationalist axis. As a result the votes of ‘others’ do not count in cross community voting in the Assembly via the current community designation nomenclature. In the not unlikely scenario that Alliance becomes the third largest party in the Assembly after 5 May this system looks increasingly unsustainable. The growth of the Northern Ireland electorate is in the centre, not at its margins and it is the non-aligned who will have the greatest impact on the political future of the region.

Standing on the steps of Castle Buildings to speak to the media shortly after Senator George Mitchell had formally closed the last session of the multi-party talks on 10 April 1998, UK Prime Minister Tony Blair gave his take on the future facing Northern Ireland: ‘The essence of what we have agreed is a choice. We are all winners, or we are all losers. It is mutually assured benefit, or mutually assured destruction.’

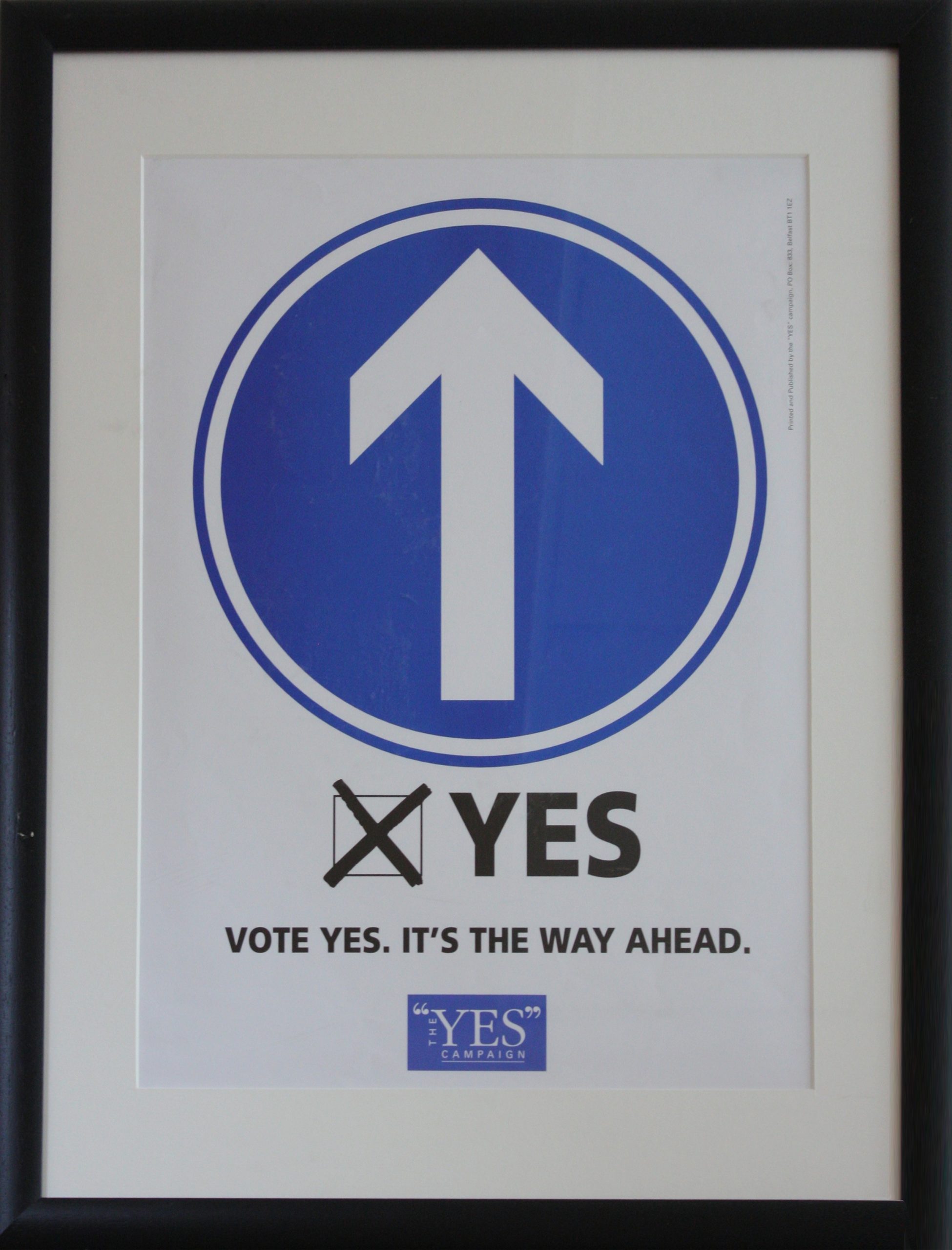

24 Years later we are still waiting to find out which of these will prevail and how our own particular political thriller will end. On 5 May Northern Ireland’s electorate will be able to give its own review of this long running franchise at the ballot box.

Feargal Cochrane is Professor Emeritus at the University of Kent and Senior Research Fellow at the Conflict Analysis Research Centre. His latest book Northern Ireland: The Fragile Peace, was published in 2021 by Yale University Press.

The views expressed in this blog reflect the position of the author and not necessarily that of the Brexit Institute Blog.

Image Credit: By Ardfern – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11517758