Cillian McGrattan (Ulster University)

The nomination by the new leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), Edwin Poots, of Paul Givan as the First Minister of the Northern Irish power sharing executive comes at a time of deep uncertainty within Ulster unionism. There are numerous reasons for this highly volatile situation and its implications for the increasingly complex and fraught triangular relationship involving Northern Ireland, the United Kingdom and the European Union remain largely unclear.

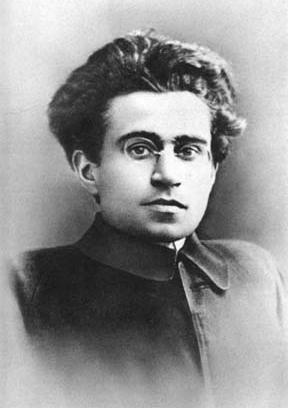

In a much-cited description of political crisis, Gramsci noted how it can appear that ‘the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear’. If Givan’s nomination is part of that crisis within contemporary unionism what might those symptoms look like?

The Northern Ireland Protocol and unionist discontent

Perhaps the most obvious symptom has been the growing unrest within sections of unionism over Brexit. At the time of writing – in the aftermath of some of the largest loyalist riots in years in April 2021, and the gathering of over 3,000 people on the loyalist Shankill Road to protest against the Northern Ireland Protocol on the eve of the G7 summit – the historian Henry Patterson’s Guardian commentary of October 2019 seems disturbingly prescient. Patterson pointed out that the DUP’s Brexit policies – in particular, its alliance with Theresa May’s Conservative government – represented an outworking of divergent class politics: The party, having supplanted the Ulster Unionist Party in 2005, straddled both middle-class and working-class Northern Irish Protestant interests. As such, it attempted to marry the anti-Brexit business community with the working-class loyalist reaction to the referendum, which integrated ‘Brexit into a vision of unionist retreat and loss during the peace process’.

This sense of loss, of course, predates the Brexit years and its contemporary configuration could perhaps be dated to the 2012 ‘flags protests’ triggered by a decision by Belfast City Council to limit the number of days the Union flag would fly above city hall. But the imposition of an Irish sea border as part of the UK’s December 2020 withdrawal agreements with the EU (specifically the ‘Northern Ireland Protocol’), precipitated increased disquiet and anger as to what the outworkings of Brexit are coming to mean for Northern Ireland.

Party politicking

In part, this disquiet has manifested itself in a complete overhaul of the DUP’s leadership – from special advisors to ministers and the leader itself. In short, the entire team associated with Brexit – from the ‘leave’ campaign run by the likes of Sir Jeffrey Donaldson (whom Poots defeated in a leadership run-off at the end of May 2021) to Arlene Foster, the party leader who carefully managed relations with the Conservative government of Theresa May under a supply-and-confidence arrangement – has been replaced by allies of Poots.

Givan’s rise to prominence is unprecedented in that he is not a party leader – Poots has preferred to remain as agriculture minister, which may be interpreted as a signal that the party is turning away from engaging at the level of nation-state politics to focus on issues central to its supporters. Indeed, through an interview in the Sunday Times Poots had been warned by the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland (SOSNI) that he should not expect to be given the same status as the First or Deputy First Ministers in terms of access to the Prime Minister, the SOSNI or be invited to events such as royal visits.

Cultural politics

The defenestration of Foster was triggered following her decision to abstain on an Assembly motion to ban gay conversion therapies – and Poots was seen as having been instrumental in pushing Foster out. Givan, like Poots, is from the religiously fundamentalist side of the party. Like Poots, he is a creationist and strongly opposed to the liberalization of Northern Ireland’s traditionally conservative laws on issues such as equal marriage. For instance, he reportedly considered rejecting a putative ministerial offer in case it would put at risk a Private Member’s Bill he introduced to the Assembly in March that seeks to amend the law to prevent abortions in cases of non-fatal disabilities. It was his decision to cut funding for a small Irish language bursary scheme in December 2016 that proved the final straw for Sinn Féin who pulled down the Assembly in early 2017. In that his appointment will depend on the acquiescence of Sinn Féin, who are demanding Irish language legislation, Jon Tonge has opined that Givan may have ‘the shortest first ministership in Northern Ireland’s political history’.

Conclusion

These types of cultural politics and existential concerns seem light years away from some of the more assertive posturing of the EU as regards the Protocol. Indeed, when looked at through the perspective of unionist uncertainty and the potential for massive unrest in Northern Ireland this summer bullish comments such as that by Emmanuel Macron to the effect that the Protocol is sacrosanct seem pathological in their representation of reality. In other words, the curtailing of considerations to EU-UK relations demonstrates a woeful lack of an appreciation of these morbid symptoms inspired by Brexit in Northern Ireland.

Dr. Cillian McGrattan is a Lecturer in Politics at Ulster University.

The views expressed in this article reflect only the position of the author and not necessarily the one of the Brexit Institute Blog.