Lee McGowan (Queen’s University Belfast)

Over Easter 2021 Northern Ireland witnessed in its centenary year some of its worst cases of sustained street violence in many loyalist areas of Greater Belfast and Londonderry since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. This manifestation of violence much from these communities is the product of growing disenchantment with the political settlement’s delivery and a disbelief that Northern Ireland’s links with the United Kingdom are ever diminishing. It is easy to focus attention on the out-workings of the Northern Irish Protocol and to portray the street violence as a temporary phenomenon. There is, however, something much deeper at work here. Feelings of unease within large sections of the unionist community have existed for some time over Northern Ireland’s future, how far the nationalist parties want Northern Ireland to truly work but importantly also, questions about the commitments of successive UK governments towards maintaining Northern Ireland in the UK. Unionists in Northern Ireland want to remain part of the UK but their insecurities are being tested with calls for a border poll and a changing demographic that has seen the diminution of the once unassailable unionist electoral majority. In short, Unionism feels increasingly isolated as its traditions, value and culture appear to be under question and unionism itself is under siege.

It was never supposed to be this way. Northern Ireland’s borders were established on six Ulster counties to establish a unionist majority, and a unionist majority that was expected to endure for the well into the future. Demographics have challenged this assumption and Northern Ireland at 100 is a very changed place. It is widely expected that the 2021 census date (when collated and published in 2022) will reveal two communities (a unionist and a nationalist one) of equals at around 48% each.

For unionists the centenary of Northern Ireland is a reason to celebrate very much in the way the fiftieth anniversary was in 1971. Yet, beyond the working class loyalist heartlands (and bearing in mind the Covid restrictions in place) there is little to suggest that there is a centenary. The fact that few major celebratory events have been planned ultimately reflects the nature of the political power sharing arrangements and very little enthusiasm from both Sinn Fein and the Social Democratic Labour Party to mark the event. This so-called ‘nationalist’ response may find explanation in the efforts of both parties to reflect the attitudes of their own support base, but it demonstrates little cross community outreach or understanding for a major anniversary in the unionist calendar. At worst, and for sections of the unionist community it simply illustrates the hostility towards the very existence of Northern Ireland itself, a view reinforced by Sinn Fein’s decision to prevent the erection of a stone monument in the shape of Northern Ireland outside Parliament Buildings.

The Good Friday Agreement had simply parked the constitutional question and skilfully allowed supporters of those favouring remaining with the UK or those that preferred accession to the Irish Republic to read their own interpretation into the agreement. Constructive ambiguity worked well in the short term and postponed any decision on Northern Ireland’s future. However, twenty three years after the landmark agreement was signed, inter-communal tensions in primarily working class areas are surfacing again as the GFA’s achievements are coming into question.

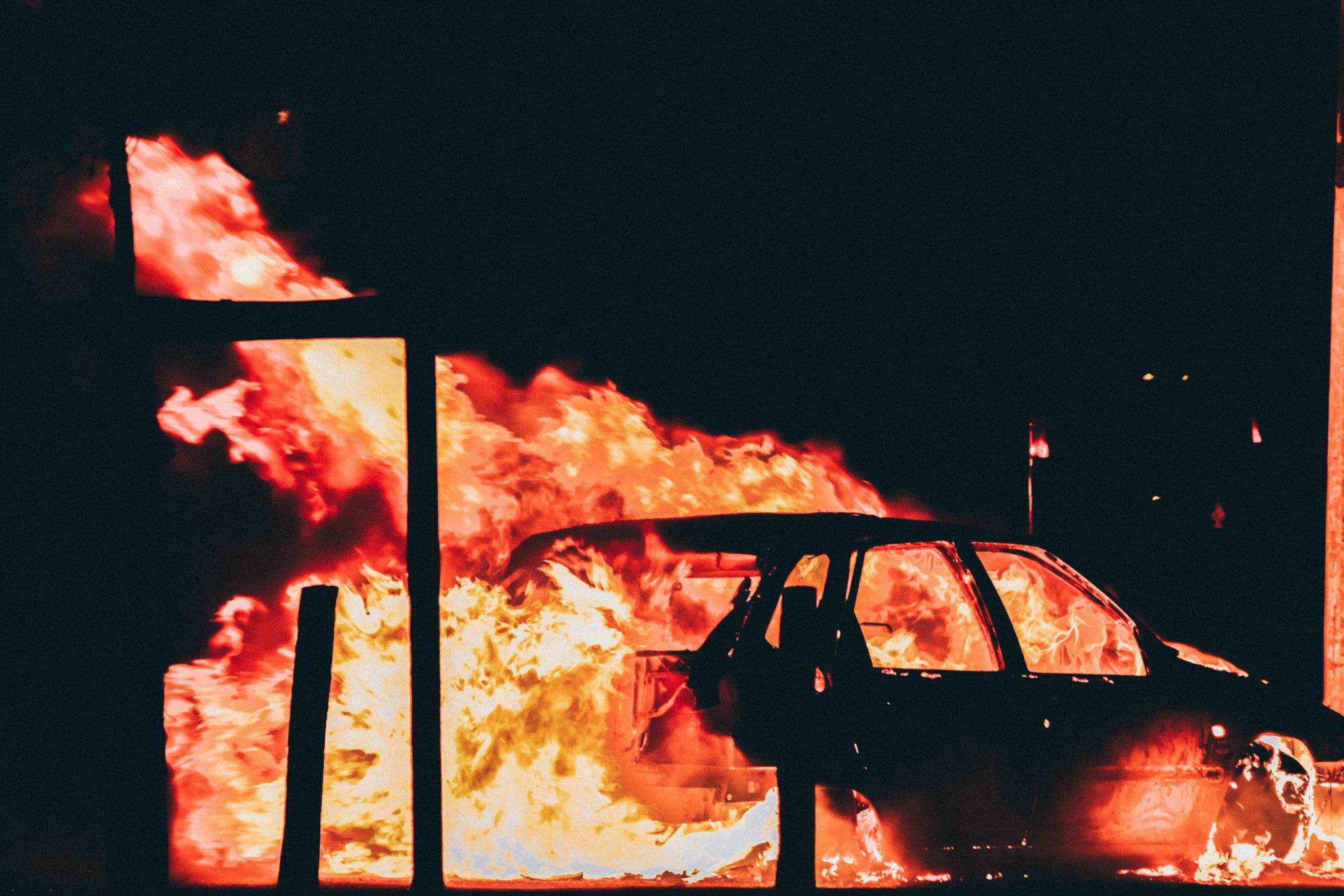

The fact that the low key 100th anniversary coincides with the implementation of the Northern Ireland protocol and a new Irish Sea border has reinforced concerns in unionist circles about the future constitutional status of Northern Ireland as a part of the UK. Again, an Irish Sea border would have been unimaginable to many unionist voters who had seen an opportunity in the 2016 EU referendum to vote for Brexit as a means of solidifying ties between Northern Ireland and Great Britain. Economically the protocol may prove to be a sizeable boost for businesses in Northern Ireland, but politically and for many sections of the Unionist community it is unacceptable. Many see the decision to place the border down the Irish Sea as a sop to nationalism and the USA at the expense of their own loyalty to the UK. At the start of 2021 graffiti declaring the Good Friday Agreement dead has become a frequent sight on gable walls in many unionist towns and city enclaves. The word ‘never’ in relation to opposition to the Irish Sea border is again hanging from many lampposts alongside more graffiti proclaiming that continued operation of the protocol means ‘war’. The language is explosive and the sentiment is raw.

Tensions have certainly heightened and street violence has taken the place of what should have been street parties in loyalist areas. Protests are set to continue but with the UK government reluctant to abandon the Protocol it is time to have new discussions about tradition, culture and respect across the entirety of Northern Irish society. Unionism faces its greatest dilemma since the inception of Northern Ireland, and how it responds will determine the power, politics and shape of Northern Ireland well into the 2020s and beyond.

Lee McGowan is Professor and Dean of Research at the School of History, Anthropology, Philosophy and Politics at Queen’s University Belfast.

The views expressed in this blog reflect the position of the author and not necessarily that of the Brexit Institute Blog.