Noreen O’Meara (University of Surrey)

The provisional text of the new EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (‘the Agreement’ / ‘TCA’) sets the scene for important shifts in the security relations between the UK and EU. Extradition is one of several key aspects of police and judicial co-operation addressed in the Agreement. It was always clear that the UK would not be involved in the European Arrest Warrant (EAW) system beyond transition, so clarity on what alternative system would govern future extradition between the UK and EU Member States was much anticipated. The outcome on surrender arrangements is a better than expected settlement, which seeks to maximise co-operation despite operational drawbacks. These new arrangements are particularly salient for EU Member States whose nationals tend to be more intensively involved with extradition proceedings involving the UK.

The TCA is now implemented in the UK via the European Union (Future Relationship) Act 2020, but with much work on practical implementation yet to do. Ongoing monitoring of rights protection and data adequacy will be crucial to the success of Part III measures on criminal justice. This post highlights selected distinctive aspects relating to extradition (without addressing termination/suspension for reasons of space).

The ‘Surrender’ system under the Agreement

The new ‘surrender’ system (Title VII of Part III of the TCA) echoes both the EAW Framework Decision (EAW FD) and the system recently implemented to facilitate EU-Norway and EU-Iceland extradition. It is based on uncontroversial templates, and should be a feasible – if imperfect – long-term solution for UK-EU extradition which applies to any arrests made under EAWs following the end of the transition period.

Much of the surrender system mirrors core aspects of the EAW system – see Hyman and Swain’s table of equivalences of help to practitioners. Striking aspects of the new surrender arrangements include the continued judicialization of surrender. The jurisdiction of the CJEU has gone, with oversight provided by the Specialised Committee on Law Enforcement and Judicial Cooperation (established by Article.INST.2). However, the influence of CJEU case law in relation to both EAW and data adequacy and retention – and its decentralised application – should continue to shape judicial approaches to surrender under the new system.

Both accusation and conviction surrenders are subject to the principle of proportionality (Article LAW.SURR.77), requiring cooperation which is ‘necessary and proportionate, taking into account the rights of the requested person and the interest of victims…’. The drafting of this section closely resembles the proportionality bar inserted by the UK into domestic law (s21A and s21B Extradition Act 2003), an element which is not present in the EAW FD. This element is ripe for scrutiny, and will keep pressure on authorities to keep up momentum in proceedings (avoiding ‘unnecessarily long periods of pre-trial detention’) and meet the time-limits carried over from the EAW system.

The new arrangements require dual criminality as the default, though this may be waived (Article LAW.SURR.79). How open EU Member States will be to waiving this requirement remains to be seen, though few States have done so in respect of the EU-Iceland-Norway arrangements. If the UK has no intention of waiving dual criminality, however, the stances of EU Member States would be irrelevant. The ‘European Framework List’ of offences survives, now with the addition of bribery as a form of corruption (Article LAW.SURR.79(5)).

Despite that, the driver of the surrender arrangements is maximisation of co-operation. This is evidenced by the limited grounds for refusal. For example, States can refuse to execute warrants for political offences (LAW.SURR.82). A nationality exception is included (LAW.SURR.83) whereby States can either refuse to surrender their own nationals, or make surrender subject to conditions. The effects of the nationality bar were already felt by the UK during transition, when Austria, Germany and Slovenia invoked the nationality exception under Article 185(3) of the Withdrawal Agreement.

Nonetheless, the additional guarantees requirements will provide extra nuance when judicial decisions to execute warrants are made. For example, where the issuing state punishes an offence with a whole-life sentence, the executing state can require a review within 20 years or clemency (Article LAW.SURR.84(a)) – evoking the European Court of Human Rights’ Vinter jurisprudence on irreducible life sentences. Furthermore, additional guarantees can be can be sought ‘where there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk’ that a requested person’s rights will be jeopardised (Article LAW.SURR.84(c)). This echoes the CJEU’s Aranyosi and Căldăraru / LM case law. One may hope that falling short of these standards is not a prospect in the UK. Yet, these guarantees underscore the ongoing nature of rights monitoring and the continued efforts on mutual trust needed by courts and authorities going forward.

An enhanced right of access to a lawyer in both the executing and issuing state in surrender proceedings is embedded among defence rights for requested persons (Article LAW.SURR.89). (This derived from Directive (EU) 2016/1919 OJ L 271/1, which the UK did not participate in as a Member State). It is good in principle to see this reflected in the text, though again this should not be controversial. There could be an interesting intersection here with situations were an individual is subject to multiple EAWs / arrest warrants in different States (Article.LAW.SURR.94).

So far, so special: losing SIS II access

The instant loss of access to the EU’s Schengen Information System (SIS II) database at the end of transition was a stark reminder of the UK’s new status as a third country. Some valuable headway was made securing participation with Passenger Name Record (PNR), Prüm, and European Criminal Records Information System (ECRIS) databases – though sometimes in modified ways. However, the limits to what the EU could offer UK on data access will bite when it comes to extradition.

Losing access to SIS II is a highly regressive step for security. This has operational implications for UK law enforcement as one of the most frequent users of the system, with some 600 million searches annually. Over 40,000 alerts related to arrest and extradition in 2019. Losing access to real-time alerts generated via SIS II mean the police are already missing opportunities to arrest wanted people, thus reducing public safety, and delaying extradition processes. Given Member States’ differing engagement with INTERPOL, relying on it as the fall-back will not make up for this operational loss for the foreseeable future.

Concluding remarks

There are features which characterised the varied national surrender systems before the EAW era which could impact the new surrender system: missed opportunities to arrest, delays and constitutional hurdles in certain States. However, the design of the surrender process illustrates well the objective of mirroring existing EAW and EU/Iceland/Norway models as closely as possible. Although the loss of SIS II is a retrograde step operationally, there is scope to hope that the surrender system offers a long-term basis for UK-EU extradition.

Its future success will demand intensified co-operation between UK and EU Member State authorities, and sustained progress rights and on data adequacy. The benefits for doing so are clear for all involved: to maintain, as far as possible, efficient co-operation on extradition in a rights-oriented process, and to safeguard the public in the UK and in EU Member States.

Noreen O’Meara is Senior Lecturer in Human Rights and European Law and co-director of the Surrey Centre for International and Environmental Law (SCIEL), School of Law, University of Surrey

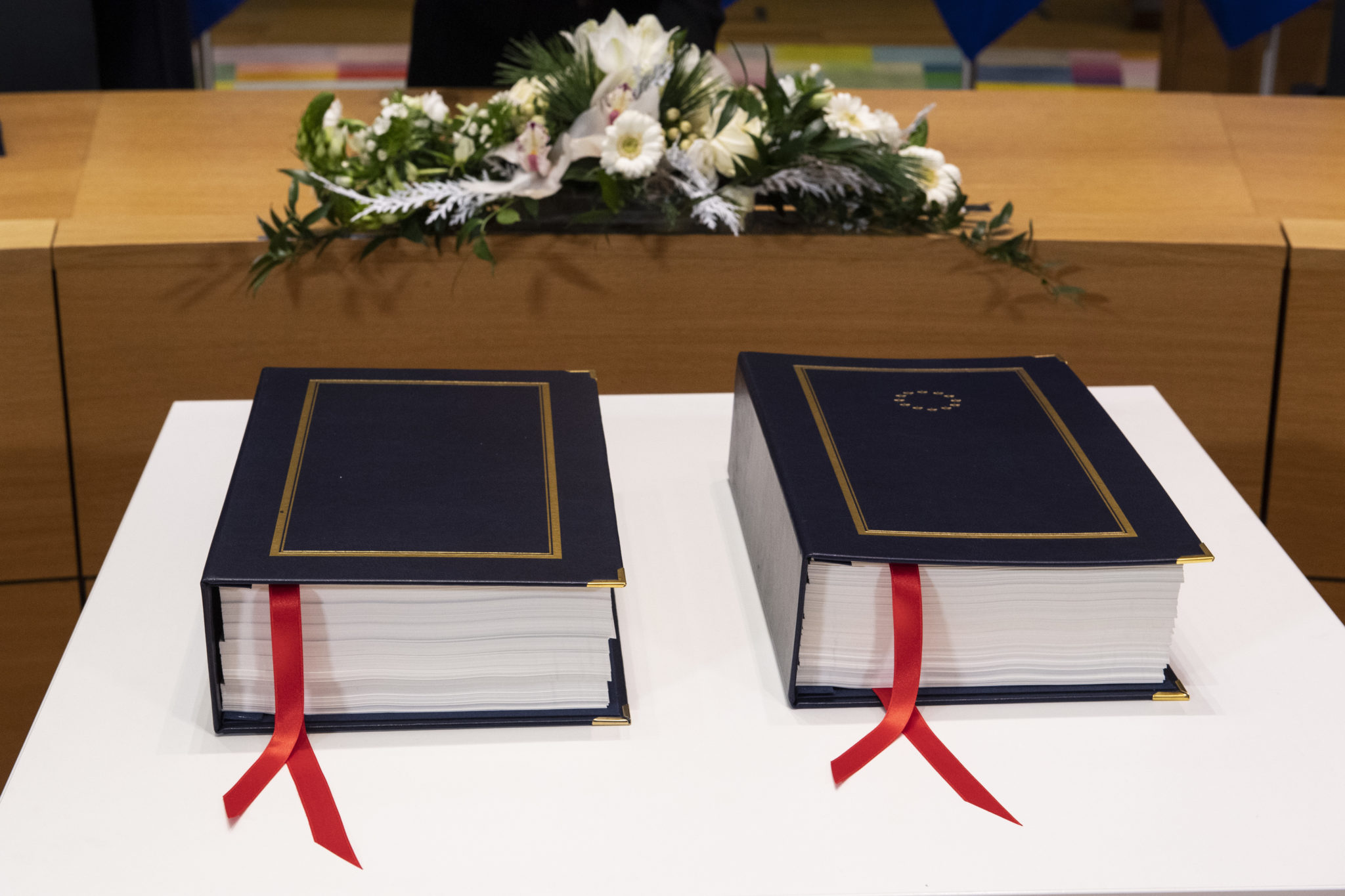

Image credit: European Commission, the signing of the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement