Oran Doyle (Trinity College Dublin)

The Good Friday Agreement, which marks its 22nd anniversary this Good Friday, built a new model of power-sharing politics on the foundation of a territorial compromise. On the one hand, Ireland and Irish Nationalists accepted the legitimacy of Northern Ireland’s status as a component part of the United Kingdom. On the other hand, the United Kingdom and Ulster Unionists accepted that Northern Ireland would only remain part of the United Kingdom for as long as a majority of people in Northern Ireland so wished it.

In 1998, Irish unification seemed a distant prospect. But demographic change was slowly producing an electorate more open to unification, and Brexit has now dramatically increased the attractiveness of a united Ireland replete with EU membership. As a result, although opinions on the likelihood of a united Ireland diverge widely, the territorial compromise of 1998 is under pressure. In this post, I will review what the Good Friday Agreement has to say about Irish unification.

The constitutional issues section of the Agreement provides that it is for the people of Ireland alone, by agreement between the two parts, to exercise their right of self-determination on the basis of consent, freely and concurrently given, North and South, to bring about a United Ireland. If this happens, it will be a binding obligation on both Governments to introduce and support in their respective Parliaments legislation to give effect to that wish. An Annex to this section of the Agreement specifies provisions to be included in British legislation. This requires that Northern Ireland can only leave the UK with the consent of a majority of the people of Northern Ireland voting in a poll.

Four important points follow from these provisions. First, the threshold in Northern Ireland is a majority of its people. There have occasionally been suggestions that a supermajority should be required, or a majority of both communities in Northern Ireland. Such approaches would breach the Good Friday Agreement.

Second, consent to unification in Northern Ireland requires a referendum. However, the Agreement does not specify what mechanism is required in the South. I have suggested elsewhere that, although it might be possible for the South to authorise unification without a referendum, the scale of accompanying constitutional change would almost certainly require a referendum. This referendum could either amend or replace the current Constitution.

Third, the consent of North and South must be concurrently given. The consents need not be simultaneous, but ‘concurrently’ does impose some limitations. In my view, the two referendums must occur under the same set of political conditions, such that there is no reason to suspect that the consent given under one would have lapsed before the other consent is given. This could occur simply due to passage of time but also due to a radical change in political circumstances. For instance, would we consider consents given before and after the onset of the coronavirus crisis as concurrent?

Fourth, and often overlooked, legislation is required for unification. Referendums in the North and South would not be sufficient of themselves to bring about unification; each Government is required to introduce legislation to give effect to unification. If the UK and Irish Government agree on the form of unification, there should be few difficulties. It cannot be assumed, however, that agreement will be easy. The Brexit process is an illustration of how difficult it can be for two parties to agree on the terms of a separation. Article 50 of the Treaty of European Union—for all its flaws—at least specified clearly the legal consequence of a failure to reach agreement. The GFA makes no such provision.

What happens if both North and South vote for unification but the British and Irish Governments fail to agree or, as happened with Brexit, the British Government fails to secure the approval of Westminster for an agreement with the Irish Government. In my view, the obligation to introduce legislation applies separately and individually to each Government. If agreement is not reached between the Governments, the Irish Government would still be under an obligation to introduce legislation to give effect to the two unification votes, and the Oireachtas is virtually guaranteed to approve such legislation. At that point, unification would have occurred as a matter of Irish law but not as a matter of UK law.

In these circumstances of disagreement, events at Westminster could play out in one of two different ways. Westminster could enact legislation giving effect to unification. In that context, residual disputes between the newly unified Ireland and the rump United Kingdom (assuming Scottish independence has not occurred) would have to be resolved through international negotiation and litigation. Alternatively, Westminster could refuse to enact legislation to give effect to Irish unification. In that scenario, Northern Ireland would remain in the United Kingdom as a matter of UK law but become part of Ireland as a matter of Irish law. It would be deeply regrettable for the constitutional status of Northern Ireland once again to become the subject of legal dispute between Ireland and the United Kingdom. In designing any unification process, therefore, it will be important to reduce the risk of such disagreement re-emerging.

The views expressed in this article reflect the position of the author and not necessarily the one of the Brexit Institute Blog

Oran Doyle is a professor in law at Trinity College Dublin. This blogpost draws on a working paper co-authored with David Kenny

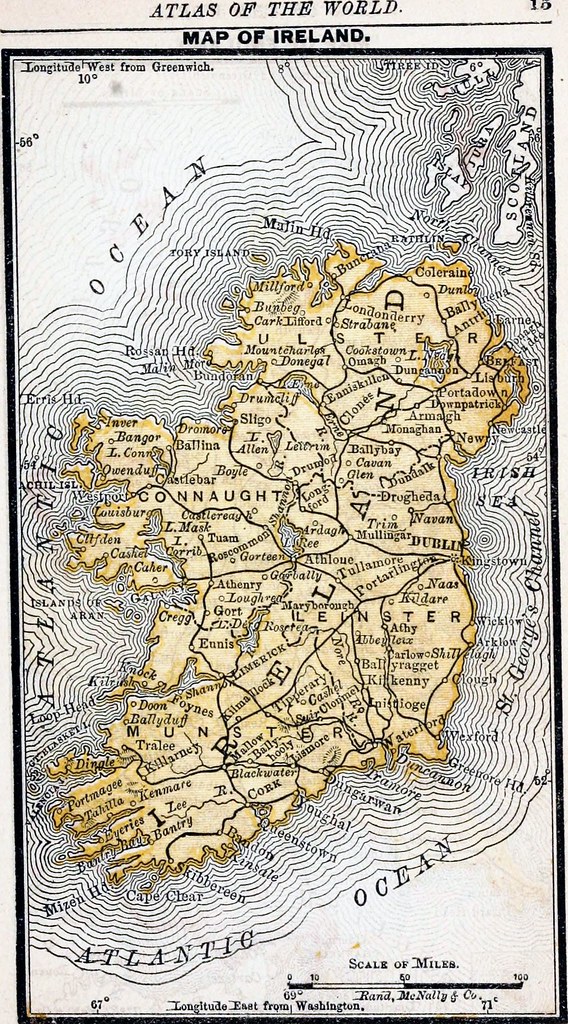

Image credit: “Ireland” by sjrankin is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0