Brexit and the Future of Transatlantic Relations

by Joris Larik (Leiden University)

Whatever the EU and UK end up deciding in their withdrawal agreement, transitional arrangement or future free trade agreement will be between them. To the rest of the world, it will be what lawyers call res inter alios acta—a thing agreed between others. Whether powerful third countries will go along with the EU’s and UK’s approach is an open question, not least in the case of the United States and its “America First” policy.

Hence, Brexit is not only a source of political and legal upheaval in Europe but will prompt a recalibration of transatlantic treaty relations. This requires proper scrutiny from both a legal and political perspective, which my new Working Paper “The New Transatlantic Trigonometry: Brexit and Europe’s treaty relations with the United States” seeks to provide. The paper scrutinizes the legal relations with the U.S. as they currently stand, as well as the transatlantic implications of the different models that exist for the future EU-UK relationship. Against this backdrop, it provides an analysis of the possible ways forward for the UK, U.S. and EU. These are three of its main findings:

First, the transatlantic impact of Brexit starts as an empirical challenge. Beyond a general sense that the UK will have to renegotiate numerous international agreements with its partners, closer analysis of official databases and compendia reveals that it is not always clear what is exactly at stake. There are, however, two consoling factors. The existing treaty relations between the U.S. and the EU and its (remaining) Member States remain in place, as will existing bilateral U.S.-UK treaties. In addition, the number of agreements to be replicated by the UK is manageable—at least for the U.S., which only has to go through this exercise once. Nevertheless, there is no time to be wasted for preparing replication and renegotiation in order to avoid unforeseen effects and protracted legal uncertainty.

Second, coping with the transatlantic fallout of Brexit requires doctrinal clarity about the nature of the relations at stake. Hence, the paper contends that transatlantic treaty relations need to be understood as both triangular and multilevel. Failing to understand the importance of how the foreign relations laws of the U.S., the UK, and the EU and its remaining Member States means failing to appreciate how the nature and content of different agreements affect their chances of successful negotiation, ratification and implementation by the different actors in the transatlantic space. These relationships, moreover, are interdependent, making their recalibration an exercise of “transatlantic trigonometry”. In particular, the close ties that EU membership exerts on its Member States, and any form of close association the UK might have with the EU in the future, will continue to loom large for any future “trade deals” across the Pond.

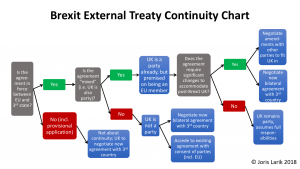

Third, achieving a “kinder, gentler Brexit” in the transatlantic context is a political challenge with many moving parts. Not only the new governments in the U.S. and UK are implementing their respective visions of “America First” and “Global Britain”, but also the EU has been propelled on a course of reform and activism in its external relations. While the near-term will be about continuity, fitting the different pieces of the transatlantic space back together is neither impossible nor an inevitability. Legally, upsetting existing relationships can be minimized, though all of this will be a matter of negotiations based on interests and will reflect the shifted power relationships. In an effort to “take back control” from the EU, to use the favorite slogan of the Leave-campaign, the UK is on a course of handing control over the fate of many international engagements to its external partners, whose consent will be required in many instances for continuing existing agreements and for putting in place new ones (see also the “Brexit Treaty Continuity Chart” below, part of written evidence submitted to the House of Commons International Trade Committee). The paper shows that avoiding disruption—perhaps counterintuitively—will be easier, at least legally, in the “sovereignty sensitive” fields of security and defense, while deeper integration and more apparent trade-offs in the trade and regulatory sphere turn the latter into the principal arena for a drawn-out struggle for the shape of future relations.

222 years ago, George Washington used his farewell address to caution against entangling the United States’ “peace and prosperity in the toils of European ambition, rivalship, interest, humor or caprice”. However, due to the many treaties that bind the two sides of the Atlantic together, and due to the immense trade flows, as well as enduring political and personal connections between them, entanglement is a given. Hence, for the sake of the future of the transatlantic relationship—to quote Washington’s farewell address once more—now is not the time to show “infidelity to existing engagements” but to recall that “[h]armony, liberal intercourse with all nations, are recommended by policy, humanity, and interest.”

Joris Larik (@Joris Larik) is Assistant Professor of Comparative, EU and International Law at Leiden University and was from August 2017 until February 2018 a Fulbright-Schuman Fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), Johns Hopkins University in Washington, D.C. This piece is based on a Working Paper jointly published by the DCU Brexit Institute and the Center for Transatlantic Relations.