Øyvind Svendsen (NUPI)

As for now, the prospects of any formal future EU-UK relationship on security and defence is in shambles. However, leaving security and defence out of the 2020 Brexit negotiations on the future relationship may have been a wise move from the UK.

Realizing that the lengthy UK process to agree on and ratify the Withdrawal Agreement with the EU led to an exceptionally short period to negotiate the future relationship, Boris Johnson’s government was quick to go back on the security and defence commitments in the attached political declaration. Theresa May had been initially pushing for the UK to become a third country like no other in the area of security and defence once they had left the EU and in the final version of the political declaration, the parties agreed to establish “a broad, comprehensive and balanced security partnership”. In the Johnson government’s negotiating paper, published just after the January 2020 exit, disinterestedness suddenly prevailed: “(…)foreign policy (…) are for the UK Government to determine, within a framework of broader friendly dialogue and cooperation between the UK and the EU: they do not require an institutionalised relationship.”

Who can blame them, really? Surely, the EU has gained momentum in the security and defence area since the British voted to leave the bloc in the summer of 2016. A new global strategy guides the union, more money is being spent jointly on research and development through the European Defence Fund and the EU has established Permanent Structured Cooperation – PESCO – in order to develop joint capabilities with the aim of promoting strategic autonomy for the EU to act in world politics. Yet, the big money is still spent at the national level.

PESCO is the manifestation of what EU researchers call differentiated integration, known also as á la carte integration, multi-speed Europe, or in European Commission jargon: “those who want more do more”. However, for most of the EU security and defence initiatives, the use of integration to describe what is going on in security and defence is conceptually imprecise – or perhaps a Freudian slip. For if integration is the formal transfer of legal competence to the EU level, EU security and defence is primarily concerned with cooperation, not integration. Within the strictly intergovernmental model through which it operates, there are few areas of broad consensus on what kind of security and defence actor the EU is or should be, and the lack of a European strategic culture contributes to the turtle-paced incremental developments that have been unfolding since 2016. Expert analyses on the topic are so hopeful on behalf of the EU that one almost loses sight of the many limitations to EU security and defence. This is not to say that EU security and defence cooperation could not become more relevant in the future, but the realpolitik of Brexit and the scarcity of time in the negotiations deems it reasonable that the UK prioritized trade over security and defence for now.

Because security and defence is largely intergovernmental, third-country participation has been fairly straight forward, albeit with limitations. Despite acknowledging those limits to third-country status in terms of access to information and decision-making, a country like Norway is closely tied to the EU in security and defence and is involved in the new defence fund as well. The UK under Theresa May also wanted a close relationship with the EU on security and defence. An early indication of a rugged path, however, was the 2018 fallout over Galileo, the EU satellite navigation system. Theresa May eventually took the UK out of the whole program because the EU denied access to the security components that eventually made it useful for military purposes. Furthermore, the UK were wary of being a decision-taker rather than a maker, and the EU increasingly came to argue that the UK would have to become a third country like any other – you can’t have your cake and eat it, you know! The problem was, of course, from a UK perspective considering its military capabilities and international diplomatic clout, that they were anything but any other third country,

The prospect of an EU army is also highly politicized in the UK. Considering that all areas of the future relationship could not be negotiated before the end of the 2020 transition period, it made sense for the UK to leave security and defence off the table. If one thing is certain, consolidating Brexit at home has been a daunting task for May and Johnson, and a strong emphasis on security and defence would mobilise deep sentiment (read fury) among most leavers – and remainers for that sake. Considering also that EU level cooperation, for now, remains fairly peripheral to the broader European security and defence assemblage, then, the stakes of not joining in are reasonably low.

A senior diplomat in the EU once described the recent EU security and defence initiatives to me in an interview as “the first pieces of a puzzle that may or may not come to completion in the future”. One’s mind quickly drifts to the ideas of integration through spill-over effects and Jean Monnet’s assertion that Europe would be forged in crisis and a result of the solutions to them. Building on the puzzle analogy, however, the recent security and defence push in the EU is the old kind of puzzle you find in the attic – it awakens positive memories of the good old days and you decide to put it together even though you know that there probably are several pieces missing and that you will never be able to complete it. Also, you know that you will not need to have it framed and put up on the wall because you already have a 45000-piece, gold-framed puzzle as the centrepiece of your living room (and because there are more aesthetically pleasing ways to decorate a wall). That centrepiece – beyond the analogy – is, of course, NATO, the most powerful military alliance to date.

Despite the hopefulness of Europeanist scholars, experts and some civil servants, the differentiated assemblage that make up EU security and defence cooperation will not rid the UK of its disinterestedness as long as NATO exists. If – or when – the alliance no longer serves its purpose, London might be prepared to fill in the missing pieces, to the benefit of not only the EU, but of Europe as such. Until then the UK is legitimately inclined to stay away – perhaps for the better on both sides of the Channel.

Øyvind Svendsen is Research Fellow at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI)

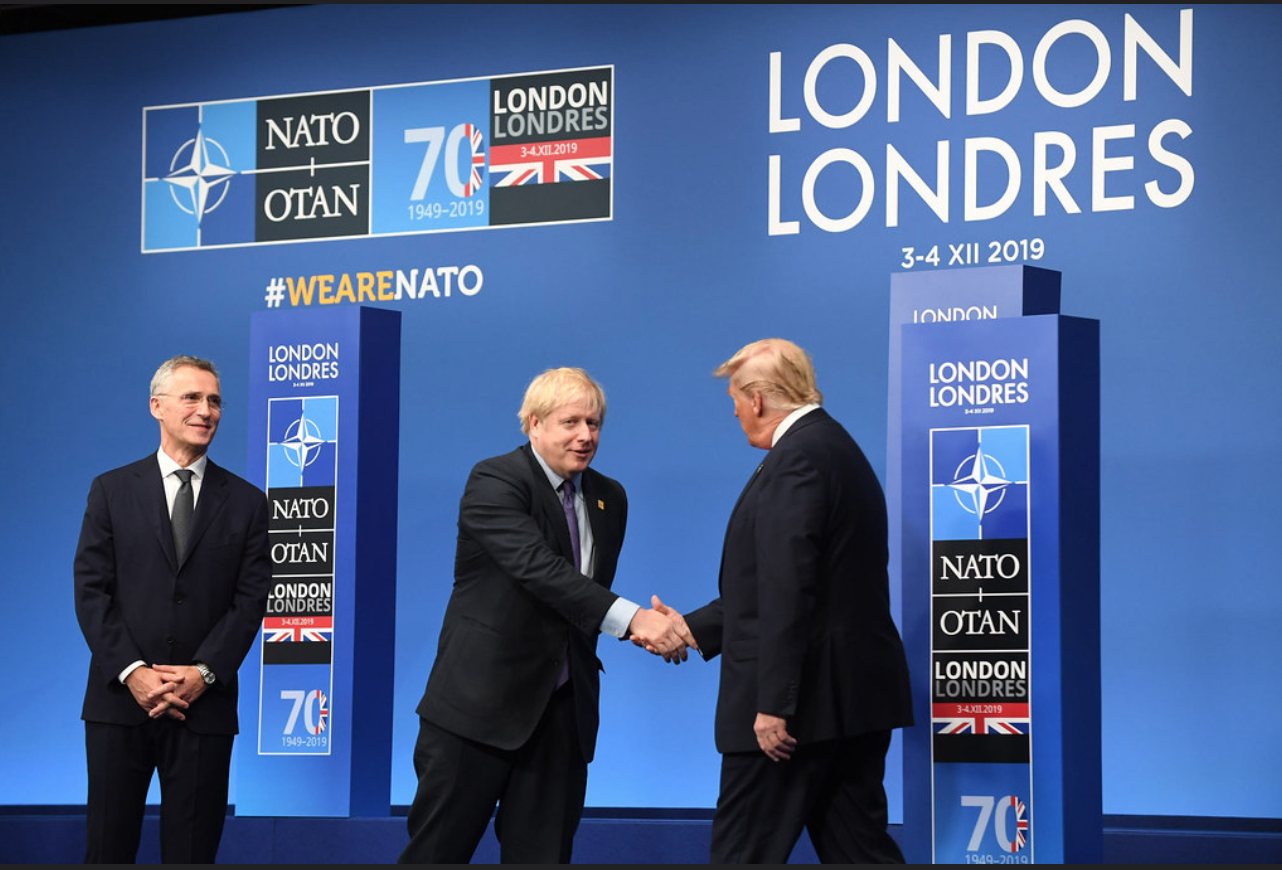

Image credit: Flickr No 10 Downing Street, The UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson hosts the NATO leaders Meeting at The Grove in Watford, 4th December 2019