Josh Hockley-Still (University of Exeter)

‘I will negotiate to the best of my ability a (Brexit) deal that will look after jobs and the economy. But the best way to look after jobs and the economy is for us to Remain.’[1]

This recent quote, delivered by Labour’s Foreign Secretary Emily Thornberry, provoked widespread ridicule. It underlined the perception that Labour’s Brexit position is unclear, a view shared by 65% of British people, according to a recent YouGov poll.[2] Yet, while it is easy to mock the inconsistencies in Labour’s Brexit policy, historical context tells us struggles over Europe are, for Labour, an issue that goes far beyond an erratic TV interview. Ever since Conservative Prime Minister Harold MacMillan announced his intention to apply to the EEC (forerunner to the EU) in 1961, both major parties have spent the subsequent 60 years grappling with an issue that does not easily fit into the traditional left-right mould of British politics.

Initially, Labour were the anti-EEC party in British politics. Its leader, Hugh Gaitskell, responded to Macmillan’s application by famously declaring that Britain joining the EEC meant ‘the end of a thousand years of history’. Yet already a significant number of Labour politicians and voters were beginning to question this stance, particularly the future Chancellor, Roy Jenkins. When Gaitskell’s successor, Harold Wilson, became Prime Minister, he was initially considered to share his predecessor’s scepticism. However, in 1967 he resurrected Macmillan’s failed attempt to join the EEC, then in the 1975 referendum supported the ‘Yes’ campaign. Historians and politicians alike concluded that Wilson’s conversion was due to politics rather than conviction. After all, the Jenkinsite pro-EEC wing of the party never saw Wilson as ‘one of them’. Nonetheless, more recent historians (most prominently Helen Parr[3]) have conclusively argued that Wilson’s conversion to the EEC was genuine.

Wilson returned as Prime Minister in 1974 after a Conservative Government finally took Britain into the EEC the previous year. He had to delicately balance a party deeply divided by the issue, not to mention his own preference to Remain. His solution was to launch a renegotiation with the EEC and put it to a referendum. The ‘Tory terms’ of membership would be gone; Wilson would stand up for Britain and get a better deal from the EEC or risk leaving. Yet, Wilson’s own preference for Remain was by this time not in doubt. Does this sound familiar? Fast forward 45 years and Labour is led by Jeremy Corbyn, also a long-term Eurosceptic who now campaigns for Remain, yet is not seen by Remainers as a true believer. If Corbyn becomes Prime Minister in a few weeks’ time, he intends to secure a better deal from the EU, then put it to the British people in a referendum, with the likelihood he will advocate Remain. (The caveat of course is that Wilson supported his own deal, rather than opposing it!)

Yet Corbyn’s link to this period is not only with Wilson. Wilson’s foremost critic in the Labour Party was Tony Benn, who was to become Corbyn’s political mentor until his death in 2014. Benn fiercely opposed the EEC on the grounds that it was undemocratic, describing a visit to the European Commission as ‘a slave travelling to Rome’.[4] He also argued that EEC regulations would render impossible his proposed socialist transformation of the British economy. In another interesting quirk of history, Benn’s son Hilary, once a prominent anti-EEC activist, has in recent years converted into one of Labour’s foremost Remain supporters. With Corbyn’s accession as leader, in some ways the party is more Bennite than it has ever been. Yet remarkably on Brexit, the biggest issue of the day, Labour’s policy is closer to Hilary Benn than to Tony.

These parallels cannot tell the full story. Irrespective of personalities, Labour is a very different party than it was in 1975. This is necessarily so; it seeks to govern over a very different country, with different norms and values. Labour is also less divided over Brexit now; only 19 Labour MPs recently defied Corbyn to vote for Boris Johnson’s Brexit deal. Wilson could only dream of such unity amongst his Labour MPs.

Nonetheless, it is worthwhile to consider the historical parallel. Wilson’s policy was subject to much of the same criticism and ridicule now faced by Corbyn’s, yet on its own terms proved enormously successful. He secured a deal, albeit with largely cosmetic changes. He won the referendum by a landslide. By giving Labour MPs (including Cabinet Ministers) a free vote, he minimized discontent within the party. Moreover, his less enthusiastic public support for Yes proved far more attuned to the public mood than the Bennite and Jenkinsite extremes. With this in mind, perhaps we should not be too quick to write off Corbyn’s Brexit policy. It may yet offer the best hope of attracting widespread votes from moderate Leavers and Remainers alike.

The views expressed in this article reflect the position of the author and not necessarily the one of the Brexit Institute Blog.

Josh Hockley-Still is a 3rd year PhD Researcher in the History Department at the University of Exeter. His thesis examines the Labour Common Market Safeguards Committee; the foremost group of Eurosceptic Labour MPs from 1975-2016.

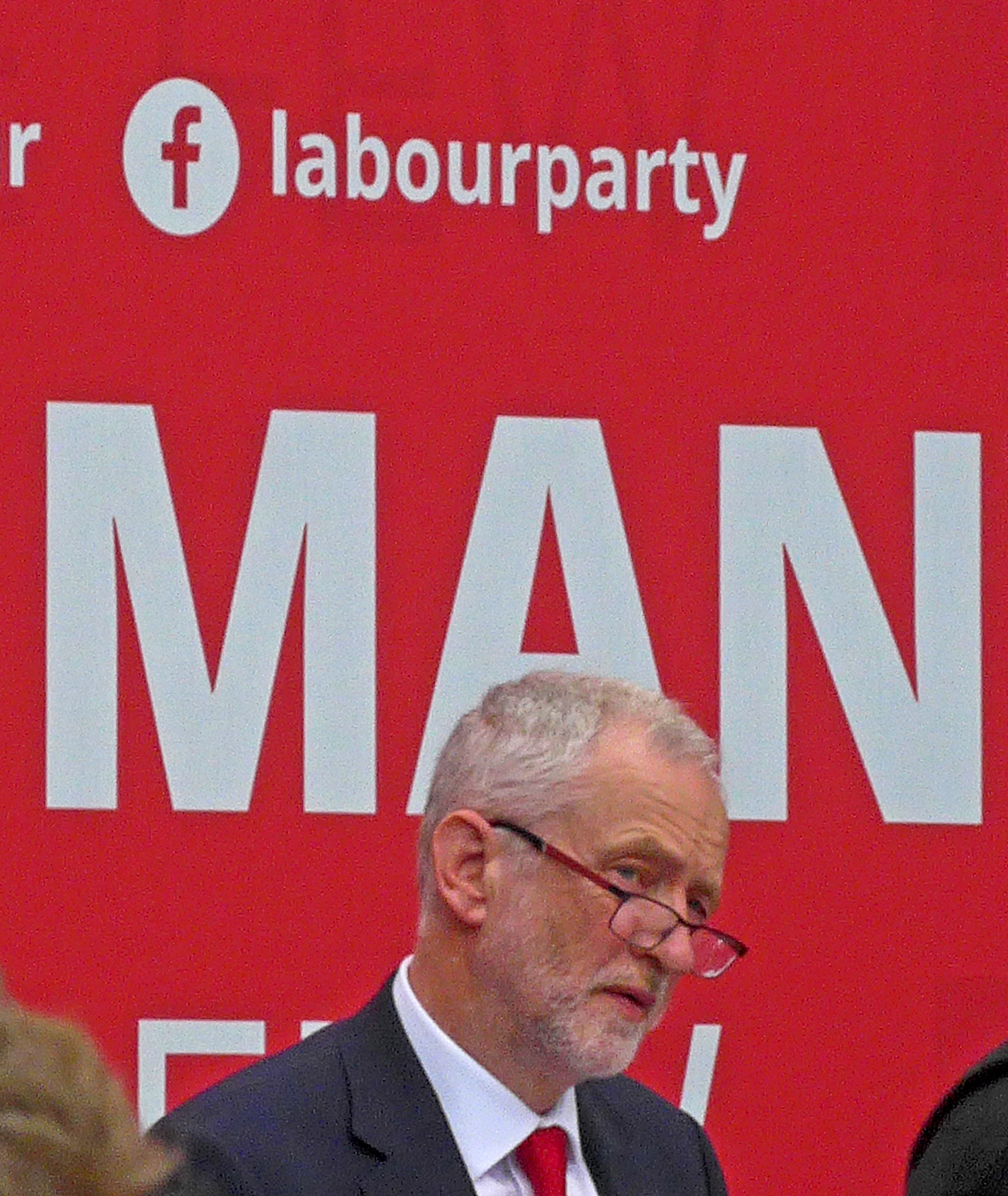

Photo credit: Jeremy Corbyn launches the 2017 Labour Party manifesto, by Tim Green under a CC BY 2.0 licence

References:

- Emily Thornberry, speaking on Question Time, 5 September 2019.

- https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2019/11/05/most-brits-uncertain-labours-brexit-policy

- Helen Parr, Britain’s Policy Towards the European Community: Harold Wilson and Britain’s World Role, 1964-67 (London: Routledge, 2006).

- Tony Benn, Against The Tide: Diaries 1973-76 (London: Century Hutchinson Ltd, 1989), p. 180.